Part Eight: South Australia

Born in Hampshire, Maria Gandy was the eldest child of a tenant farmer William Gandy and his wife Mary Ann. Her mother’s premature death in 1832 left Maria (pronounced Mariah), aged 21, ti bring up her three younger brothers: George (b. 1813), William (b. 1817) and Edward (b. 1825). Furthermore, by that time, William Gandy Senior was also ailing; he was suffering from tuberculosis. Unable to continue farming, he took a job as caretaker at a manor house owned by an army major in Twyford. The boys helped their father doing odd jobs about the house and grounds and Maria became the housekeeper. It appears that she was also an able seamstress and earn extra money for the family by making dresses for clients in the village.

In 1832, William Light took a lease on the house when its owner was posted to Canada; he himself had recently been diagnosed with tuberculosisand had been advised to move away from the unhealthy climate of Egypt to Twyford whose weather was thought conducive to consumptives. If he hoped to move there with his wife Mary, it was not to be. He was in England on business for the Pasha of Egypt but on his return he learned of the infidelity of his wife Mary in his absence – and her pregnancy. His marriage was over. Whether he was already involved with Maria Gandy or not is uncertain. Light was already showing concern for the Gandy family, however; his papers at the time record personal payments to both William and Maria. On his next visit home, Light also wrote in a letter that he was eager to return to Twyford for it was where his heart was.

In 1836, William Gandy Snr died just before William Light was to embark on his great voyage to Australia. There seems no doubt that by then he and Maria had entered into a relationship for he brought her and young William and Edward with him on the Rapid. Their older brother, George, now a brickmaker and married himself, opted to stay in Hampshire but later also joined his sister and brothers. The life of Mariah and William in South Australia is detailed in Part Eight of Legacy.

It was obvious to all that they were cohabiting, considered scandalous in the tight knit settlement whose residents held rigid Christian principles. As a result, polite society shunned Maria, although generally accepted Colonel Light, who was, of course, ultimately the man responsible for the successful establishment of the city of Adelaide. Even he, however, suffered on account of his mixed heritage and no doubt his unorthodox relationship, which was judged as further proof of his uncertain morals. Even the progressive thinker, Lady Jane Franklin, who had been a close friend of William and Mrs Light in Alexandria spoke scathingly of ‘his mistress in Adelaide’ even though she knew Light’s predicament having been abandoned by his wife. Had Light been free to marry, he most probably would have regularised his union with Mariah. But he was not.

There were others in Adelaide, most notably the Woodfordes and the Finnesses, however, who were sympathetic to their union and visited the Light household regularly. The surveying community was firmly in their camp. But people still turned their back on Maria in the street; Reverend Howard of Holy Trinity Church (the first chapel in Adelaide) refused to speak to her. When William Light built Theberton Hall on the outskirts of the settlement, he intended it to be a safe place for his wife after he was gone, for by then he was already very ill with consumption.

In his will, William Light made Maria Gandy his sole heir, although her name was almost completely missing from any of the biographies and histories of the time, other than as Colonel Light’s ‘housekeeper’. It was almost as if she did not exist. Yet Maria nursed William through his final illness and did indeed inherit Theberton Hall when he passed away in 1839.

The following year, Maria married an Irish doctor, George Mayo, who was to become a man of considerable standing in Adelaide. They had four children: Mary Jane (b. 1841), Kate (b. 1843), George (b. 1845) and Maria Louisa who died as a baby in 1847. Sadly, Mariah herself, after years of nursing her father and her partner went on to contracted TB herself. She passed away at the end 1847 at the age of 36 and was buried in an unmarked grave in West Terrace Cemetery along with her little daughter.

There has been much discussion about why Maria’s grave remained unmarked. It was a double plot – had Mayo initially intended to build a memorial later for them both? His second marriage to Ellen Russell in 1851 with whom he was eventually buried, may well have sidelined this plan. It certainly seems a pitiful oversight that echoes Maria’s general lack of acknowledgement in Adelaide history.

In 2011, on the bicentenary of Maria’s birth, a memorial was finally erected to her by the local residents of Thebarton near where she had once lived with William. The rectangular marble structure is marked on each of its four faces with the legend: Carer, Pioneer, Mother and Settler, at last recognition of the role she played in the early days of Adelaide. Maria Gandy was so much more than a mere housekeeper!

Maria Louisa Gandy (1811-47)

This may be the only existing image of Maria Gandy.

From Light’s notebook during a trek he made to Encounter Bay in 1837. It is known Maria rode with the party as far as Glenelg.

The River Itchen in Twyford, Hampshire

[Photo credit: www.cruise into history.com]

HMS Rapid by William Light 1836

[Library of South Australia Collection]

Col. Light’s cottage at Thebarton c. 1916

[Gustave A Barnes, Art Gallery of S. Australia Collection]

Plaque marking the site of Theberton Cottage. Port Rd, Thebarton

Erected on Bicentenary of the birth of Maria Gandy in 2011

Albert Street, Thebarton

“On the banks of the Torrens, at Thebarton, formerly the residence of the late Colonel Light, a substantial brick-built house, containing four large and lofty rooms, one underground and a back kitchen-commands a fine view of the bay-a garden in a high state of cultivation-a stable, with saddle room-and a well of capital water.

Apply to Dr Mayo, Carrington Street, or to Mr Gandy, on the premises.”

John Hindmarsh (1785-1860)

John Hindmarsh was a navy man through and through, having possibly joined at the age of five as ‘servant’ to his father, Captain Hindmarsh of the Bellerophon. Midshipman Hindmarsh had the good fortune to come to the notice of Admiral Nelson at the Battle of the Nile (1798) when he intervened to put out a fire that threatened to spread to the Bellerophon after most of its officers had been killed - he was later promoted to Lieutenant on the Victory on the strength of it. He served on HMS Phoebe at the battle of Trafalgar in 1801.

Then came a long period when Hindmarsh’s career seemed to stagnate somewhat. He was part of the fleet in Java expedition in 1811 serving as lieutenant on the Nisus and, although he was promoted to Commander in 1814, the Peace after the defeat of Napoleon forced him to spend a long period ashore on half pay until he was finally promoted to Captain of HMS Scylla in 1831. Although unemployment is not an untypical story for military/navy personnel at the time, to wait until the age of 46 to make captain suggests that Hindmarsh had failed to make an impression as a leader.

In 1834, Hindmarsh was the first naval captain to respond to Colonel William Light’s recruitment campaign to join the new Egyptian navy being built by Pasha Mehmet Ali. Although Light was his superior officer, Hindmarsh took a rather superior attitude to him, which may indicate that he disapproved of his mixed heritage. He demanded that Light hand over the command of the paddle steamer the Nile to him. Light also seems to have been unimpressed by Hindmarsh’s general seamanship, which must have irked Hindmarsh, who was desperate for advancement and seemed to blame Light for his lack of advancement in Egypt.

In Alexandria Hindmarsh was particularly incensed when he realised that the Pasha did not intend to give him the overall command of the Egyptian navy. Refusing to serve under a French admiral, he soon resigned his commission to return to England. Colonel Light asked him to deliver a letter to Charles Napier on his arrival in Hampshire – and in a curious act of oneupmanship, he took advantage of Napier’s confidence (that he had refused the role of First Governor of South Australia) to lobby the government for the position himself, successfully replacing the current nominee, who was none other than William Light himself!

In 1836, Hindmarsh set out on the Buffalo for South Australia, undergoing a difficult crossing that was mostly the result of his bad decisions, reinforcing Light’s opinion of his seamanship and leadership. The difficult relationship between Hindmarsh and Light is explored in Legacy Part Eight, culminating in Hindmarsh’s recall from his post - and Light’s resignation. He was not popular amongst the settlers.

In 1840 on his return to England, Hindmarsh, despite the criticism against him in Adelaide, was appointed Lt. Governor of the island of Heligoland, recently acquired from Denmark. He remained in this post until his retirement in 1857. There may be criticisms of his abilities but he was certainly an able careerist! By the time he retired, Hindmarsh had reached the rank of Rear-Admiral in the navy. He was knighted in 1851 by Queen Victoria. The name Hindmarsh is a common place name in Adelaide and its environs.

John Hindmarsh c. 1849 by Buchheister

[State Library of South Australia]

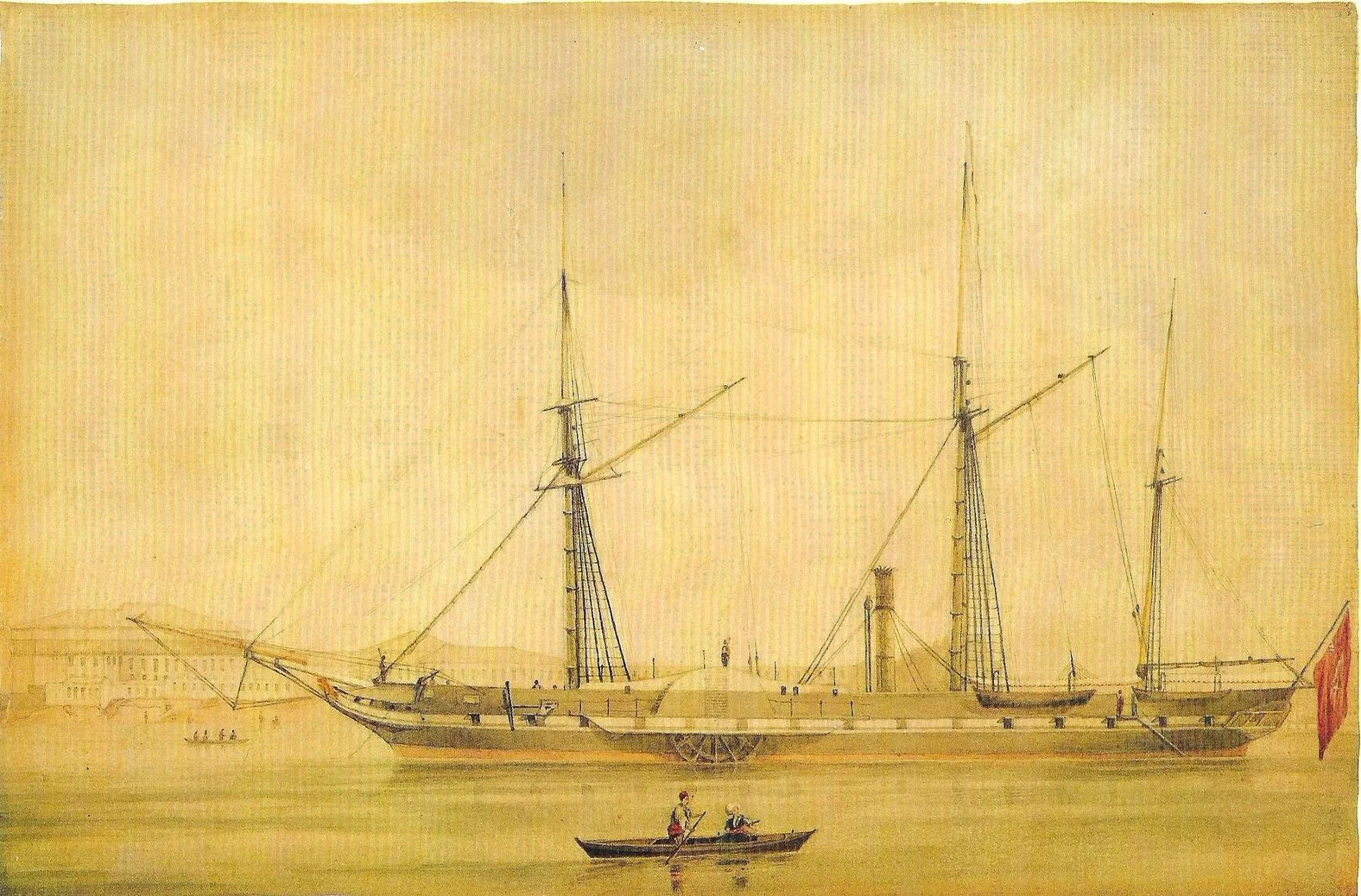

The Steamship Nile 1834; Watercolour by William Light

[Adelaide Town Hall, Presented by A. Francis Stuart 1931]

The proclamation of Adelaide Dec 28th 1836

[Artist: Charles Hill c. 1856. Art Gallery of S. Australia]

Sir John Hindmarsh 1856

[Photograph taken by John Jabez Paisley Mayall, London]