Prince of Wales Island: Tea and Sympathy

Originally placed between Chapter 2 and 3, this episode introduces us to a few members of the new administration of Prince of Wales Island, Lt Governor Leith, former Assistant and Acting Superintendent George Caunter and the newly arrived Assistant Superintendent William Edward Phillips, who will be responsible for the construction of Suffolk House a few years later. All these people feature in later chapters in some form or other. Several historical events are also mentioned which will be referred to elsewhere. Thus, most of what the scene contains may be viewed as redundant. One aspect however is important to me and I regret its loss: the issue of British Company men who took wives from the local community. By 1800 this practice was viewed with much more disapproval than in the generation of men like Francis Light, and could quite easily end a man’s Company career.

George Caunter 1758-1811

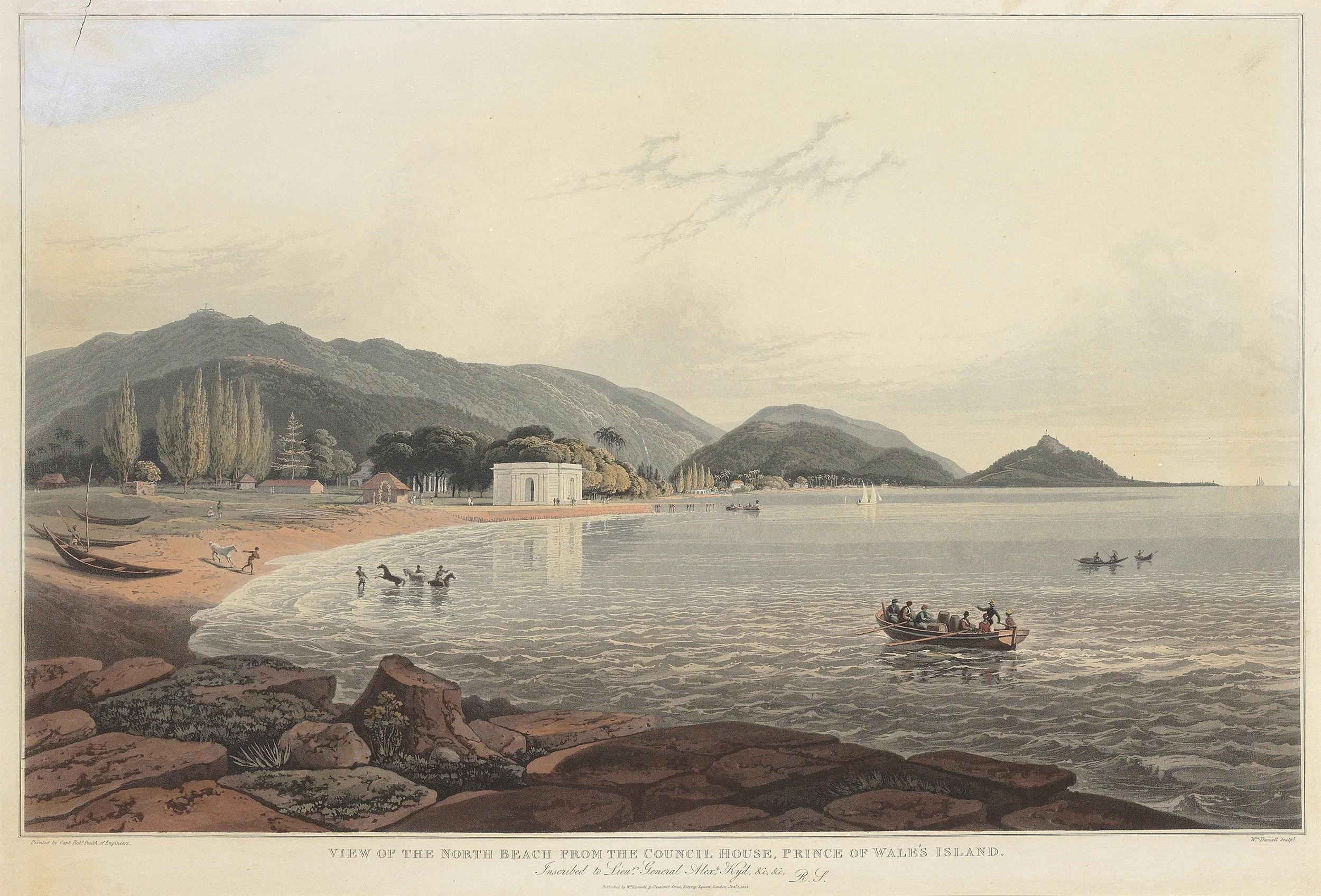

Government House 1818 by Capt Robert Smith

Major Sir George Alexander Leith (1766-1842)

Government House, Prince of Wales Island, May 3, 1800

…As he mounted the steps of Government House, the bitter taste of resentment rose like bile in his throat. Not so long ago as Acting Superintendent, George Caunter had presided over these hallowed halls, only to be tossed aside by the arrival of this new administration. Not that he didn’t have a shrewd idea as to the reason he had been passed over, but his supposition gave him no immediate consolation. It only added to his sense of injustice.

Close up, the once impressive edifice of Prince of Wales Island’s first brick building revealed it had not aged well. Exposed as it was to the elements on a windswept beach, a combination of salt, sun, storms, the inevitable damage of the moist climate and a voracious insect population, Government House was now a tawdry version of its former glory. Its white stucco exterior was patched with creeping mould; greenery sprouted willy-nilly from cracks and joints, window frames rotted and crumbled away; shutters hung loose. The roof was a patchwork of broken tiles and poorly done mending. Epicaricacy, that unworthy– but entirely pleasurable –enjoyment of the misfortune of others, possessed him. Neither Leith nor Phillips, the newly arrived governor and his deputy, would find the place amenable, which gave him some bitter comfort.

Dismissing such low notions by reminding himself that, unlike others less fortunate, he at least still held a role in the new administration, Caunter took the steps two at a time and entered the hallway. A musty smell assailed him. Even the brass bowls of fragrant spices and pandanus leaves crowned with hibiscus flowers could scarce conceal the rot. A young writer emerged from within – a boy he had personally appointed! –motioning him to enter the meeting room, as if he didn’t already know its whereabouts. How quickly allegiances are transferred.

The meeting room was a large airy space with a sea view, its tall French windows wide open, curtains blowing in a fresh sea breeze. A group of men were already gathered, he the last to arrive. The solid teak table around which they sat was the most elegant piece in an otherwise sparsely furnished room. Polished to an unnervingly glassy finish, it distracted from the general shabbiness. It was laid with the makings of an excellent afternoon tea. A buzz of congenial conversation met his ears.

‘Welcome, Mr Caunter. Please take a seat.’ Lieutenant-Governor Major George Alexander Leith rose to his feet, ushering him into a chair on his own left, a prominent position considering his new circumstances.

‘I hope I have not kept you waiting, gentlemen,’ Caunter replied, although he knew he had arrived exactly on the hour. The sycophants had arrived early of course, he observed, still finding fault at every turn, unwilling to set animosity aside. Yet he could not ignore his allocated seat at the table. Leith had honoured him with a senior position.

‘No need to apologise, sir, you are not at all late. And even if you were, no matter. Despite its formal setting, this is not a formal Council meeting, as I stressed in the invitation. Indeed, I would have preferred for us to meet in the parlour, but it’s not in a fit state for visitors, I’m afraid. Poor Government House requires rather a deal of work, wouldn’t you agree?’

Caunter took his seat with a curt nod, wondering if the new governor’s comment was in fact a veiled criticism. Were they implying he should have done more during his time in charge? Where did they think he might have found the resources for such beautification when he had been struggling to contain the chaos left by of MacDonald’s hapless administration? But Leith did not appear to be chiding him as he carried over the teapot from a warmer on the side table, a broad smile on his face. ‘I’ll do the honours while you fellows help yourselves to the excellent fruitcake. Thus, once fortified, we shall have an amicable chatter about this and that. We’ve a mighty task ahead of us but must first establish good relations so that we may work together as a team, all singing from the same hymn sheet.’

George Caunter took the proffered fine bone China cup – the service must have arrived with the governor as none such had existed in his time – and a slab of what did indeed prove to be an excellent cake. Introductions were made between those meeting for the first time, followed by genial conversation. Those who knew each other caught up on local gossip, filling in the newcomers on some of the more noteworthy recent happenings. By the time they were ready to address formal matters, an amiable atmosphere had been established during which each member of the group had tested the mettle of the others. Leith had demonstrated his light but shrewd hand in bringing together the local officers and the ‘interlopers’. Despite his initial reservations, Caunter was quietly impressed by the man.

The new Lieutenant–Governor of Prince of Wales Island, was already a man of some distinction, a senior military officer of the Indian army fresh from his pivotal role in the great victory at Seringapatam and the final defeat of Tipu Sultan, that intractable thorn in the British side. His designation as lieutenant-governor not only reflected his prestige but also signified that the Company was finally ready to raise the status of the island. If this was Leith’s reward for his service, it further proclaimed Prince of Wales Island second only to the three great Presidencies of India. Aside from the laurels heaped upon him, Leith was a man of excellent reputation, renowned for intelligence, honesty and prudence quite as much as strategy and courage. Only a fool – or corrupt traders who preferred a weak administration – could quibble with his appointment. Even George Caunter admitted that much.

The Lieutenant-Governor was a solidly built man of average height with florid heavy features saved from severity by deep-set twinkling brown eyes. His appearance was always impeccable: elegant dress uniform, neatly cropped grey hair, proud bearing. Leith possessed an air of authority worn lightly– yet there was no question that he was the man in sole command. As soon as he entered any room it was always his, drawing every eye. The unexpected informality of this first awkward gathering meant that these very different men were already relaxed. Caunter noted the ease with which Leith had created such a conducive atmosphere. It spoke volumes about the man. As they all continued refilling cups, passing the sugar, picking dainties from the plates, they were now far better disposed than when they had entered the chamber. With rapport firmly established, Leith deftly embarked upon the business of the day.

‘I wish to begin by welcoming you all to Government House, a place already familiar to some. Mr Caunter here has held the reins for nigh on five years already as Assistant Superintendent, an extraordinarily heavy burden for the paltry salary of Secretary. On behalf of the Bengal Council, I hereby thank you most sincerely for your service– in particular your dealings with our fractious local sultans. Make no mistake, Mr Caunter, your efforts have been noted.’ Leith began a round of applause that was immediately picked up by the others, bringing a flush of pride to George Caunter’s angular face, revealing an unexpected boyishness to a man whose dark, hawkish good looks often gave the impression of haughtiness. He had not expected recognition; this simple act of gratitude went a long way towards assuaging his resentment. Sometimes all a fellow required was to be thanked.

‘It was my duty, sir, one that I was honoured to carry out,’ he answered solemnly.

‘Just so, but all the same, praise should be given where it is due,’ replied Leith with an easy smile. ‘To all intents and purposes, it may seem your role has now diminished, but I assure you this is not to be the case, sir. You are reinstated to your original post of Assistant Secretary, which holds the status of third officer on the Council. It also now commands a higher remuneration. Furthermore, as your local expertise is invaluable to us new men, I intend to make the best use of your experience in an advisory role attached directly to my office. You will be my eyes and ears in the region, so to speak.’

‘Thank you, sir. An excellent idea,’ Caunter replied with a formal nod, although inside his heart was racing. Leith was proving to be a fine fellow, quite the opposite from what he had expected. As special aide he gained a very influential position. For years George Caunter had indeed run the island on his pittance of a salary with little support or guidance. The calamitous administration of Superintendent Forbes Macdonald and the free-for-all that had subsequently broken out, had cast Prince of Wales Island in a very bad light in Bengal. Caunter had thus feared his involvement might have blighted his career, but it seemed the very opposite was the case.

Mutterings around the table indicated that the general opinion found Caunter deserving of this commendation. ‘There is more, sir,’ Leith continued. ‘You have worn several other hats these past years, duties which you have also performed meticulously. I note that you are Acting Chaplain and Registrar of Births, Marriages and Deaths? Is there no end to your abilities?’ the governor added generously. ‘Until we finally secure a permanent vicar for the island and build a church–surely long overdue–may I presume you willing to continue in this essential, if humble, duty? There will, of course, be a small stipend to go with it.’

Caunter gave a tight smile. He had rather hoped this annoying task might be passed to one of the junior men. Yet he could hardly refuse such a gracious request. ‘Of course, sir. I would be honoured to continue in the role.’

‘Excellent. And in the temporary absence of our new judicial appointee – I believe Judge Dickens will be arriving in a few months– may we still rely on your services as magistrate? If that is not too great an added burden?’

Caunter bowed his head in acknowledgement. This was one responsibility he believed himself well suited for particularly as it carried a great deal of status and authority of its own. The dispensation of justice placed him in a position of influence amongst both European and native settlers alike. ‘Of course, sir. I have been ably assisted these years by Mr Manington. It seems entirely fitting that we should continue this arrangement if it pleases your excellency until Judge Dickens is in place. The cutcherry is currently established in one of my properties, a decent brick building on Pitt Street. I’m willing to continue offering its use until such time we have a proper courthouse.’

‘I was hoping you would agree to that. Mr Caunter you have been most amenable. Everything is settled then. Arrange a suitable lease for the building and make the necessary improvements, eh? May I leave that in your hands then, sir? As you are also Acting Treasurer, I am sure you will come to a satisfactory arrangement with yourself regarding the payment of the lease, eh? Thank you, Mr Caunter. Do you have any other matters you wish to discuss?’

A titter of polite laughter carried around the table at Leith’s acknowledgement that a certain amount of personal financial gain for officers was expected. Caunter shook his head. ‘No, sir. Everything is most satisfactory.’

‘Then I shall move on, if I may – but perhaps you could give me a few extra minutes after the meeting has dissolved? I have another private matter to sound out with you alone.’

This time the curiosity of the members was piqued, only adding to Caunter’s satisfaction. He would know things that the others did not. It was the perfect salve to apply to the wound of his resentment.

Leith next addressed the difficulties encountered over the past years. In defence of the previous governor, Major Forbes Ross McDonald had himself inherited a troubled administration reeling from the deaths in quick succession of Francis Light, his successor Philip Manington Senior and Secretary Thomas Pigou, so some leeway had to be accorded. Yet rather than steadying the ship, the irascible McDonald had driven a deep wedge between the merchant community and the Company. Whatever the wrongs and rights of the subsequent standoff, ably fomented by the equally curmudgeonly James Scott, the administration had suffered a serious blow. Conflicts and accusations had ignited the two camps, encouraging further corruption and abuse.

Leith intended to change all that, as did the Governor-General. Fresh from the defeat of Tipu Sultan and the routing of the French from most of India, Sir Richard Wellesley’s hands were now relatively free to take stock of the status quo in the Straits. Unlike Cornwallis before him, not only was he inclined to look more favourably on Prince of Wales Island, but his younger brother, Colonel Arthur Wellesley, had personally written a glowing encomium of its potential. The Company was now primed to invest more fully in this excellent establishment. With a gesture to the gentleman on his right, George Leith announced grandly, ‘May I now introduce my Secretary Mr William Edward Phillips, who served with distinction at Seringapatam? As second in command, he is my deputy in all things. Mr Phillips hails from a distinguished line of military men. His own father, Major-General Phillips, gave his life in America in ’81. We are fortunate to have a man of his calibre in our administration.’

Throughout his formal introduction, Phillips had unwisely assumed an expression of such smug self-satisfaction as to immediately alert those who did not know him to the specifics of his character. William Edward Phillips possessed an unremarkable face that might have been passingly pleasant if not for his oddly receding hairline that gave the impression of a peeled boiled egg. His features were blandly forgettable, his mouth habitually arranged in an ingratiating smile, his eyes overly solicitous. It was almost as if he was posing in a mirror the better to impress the public of his sincerity. Instead of drawing people to him, however, his demeanour succeeded only in keeping them at bay. Not that Mr Phillips had the slightest understanding of this effect, believing everyone to be most impressed by his congeniality. His self-satisfaction did not escape the notice of Major Leith whose sharp eyes had quickly registered the recoil of the others.

‘Whilst Mr Phillips is a most able Company man, he has little prior knowledge of the Straits – or of civilian administration, being previously a battle-hardened soldier, much as I. I’m sure you more experienced fellows will extend a helping hand to both of us in the future.’ And that was the extent of what Leith had to say about his eminent assistant.

If there had been any implied slight, Phillips himself was impervious to it. ‘Thank you, Lieutenant-Governor for your introduction. The mismanagement of previous administrations has been woeful. I intend to sweep out all the bad practices. One of my first tasks is this very building. Look around you, gentlemen! Government House is crumbling around our ears. Mould, infestation and rot, ceilings in disrepair, holes in the roof. Meanwhile, the sea edges nearer every day until it seems we may soon be swept into the strait! Furthermore, that rogue James Scott is now our landlord, charging an extortionate amount for the privilege of keeping us in such squalor!’ Phillips looked accusingly at George Caunter, reminding them that this arrangement had come about during his time as superintendent. ‘The building of a new residence – one of prestige as befits the future status of this settlement– must take priority above all else!’

Rising to his feet, Phillips grandiosely indicated the various flaws in the room. Chunks of plaster were peeling from the walls, the curtains were faded and in need of a stitch here and there, and several containers were dotted about, no doubt to catch the many roof leaks when it rained. The pervasive smell of mildew hung about the room despite the open windows.

Captain Norman Macalister, head of the military, spoke up. ‘I’ve been on this island for many years, since the days of good Superintendent Light himself. To be fair, Mr Scott’s action in purchasing this house was as a protection to the Light family legacy, of which he is the legal trustee. I must point out that the Company had fallen into arrears in the payment of the lease, much to the detriment of the Light family fortunes. Scott’s intervention and Mr Caunter’s subsequent action has led to the payment of what was due to them. Scott also raised much-needed capital for Mrs Light by purchasing Government House into which Superintendent Light had sunk a great deal of his own fortune on behalf of the administration–’

‘–There is no such person as Mrs Light, captain. The ‘lady’ to whom you refer, one Martha Rozells, or some such name, is a Eurasian woman of Siam who has already apparently found herself a new husband with the speed in which these native temptresses change their partners,’ Phillips chuckled. ‘I would not concern myself in the least with her affairs, sir. She has done well enough out of us already. And Mr Scott has done even better out of her!’

Macalister’s freckled skin blushed at the slight, but before he could counter, Leith took the floor again. ‘A debt is still a debt, Mr Phillips, no matter to whom it is owed. We must be seen to apply the same rules for all, British or native alike. I understand your concerns about the building, but it is in no way the most urgent matter in hand. We’ve been soldiers living on the march. I’m sure a little discomfort can be endured for the time being.’ In a few sentences, Phillips had undone the genial atmosphere set by his superior, offending almost everyone who had served on the island, entirely confirming their original impression that Phillips was a vainglorious and self-serving fool. Leith’s clarification was timely indeed but not well received by his deputy, whose pursed lips and flushed skin revealed his annoyance at being opposed.

The discussion moved on to one of the younger members of the gathering, Philip Manington, son and namesake of the late lamented Superintendent Manington who had taken over the reins onLight’s sudden death only to follow him into the graveyard himself but a year later. Young Manington was to be tasked with undertaking a thorough survey of the current landholdings and available plots on the island. ‘It is essential that we establish a sound legal basis for every square foot of land,’ explained Leith. ‘ Each entitlement must in future be backed up in newly issued legal documents. We must also place a reasonable limit on what one man may hold to guard against vast private monopolies. Application of the law is the only way to nip such corruption in the bud.’

‘Mr Scott and his friends will have something to say about any attempt to limit their control. He owns half the property on the island!’ Phillips broke in, without considering if any of the men present might fall into the definition of ‘friends’ of Mr Scott. He was oblivious to courting his peers.

‘Fear not, Mr Phillips,’ Leith continued. ‘I intend to proceed carefully and suggest we all do the same. I will consult the significant landholders of each community so that we can come to some sensible agreement. And that includes the Company and all its people, which comprise the majority section of landownership on the island. Indeed, this survey may lead to the release of civic funds for public projects for the benefit of all by the enforced sale of unused holdings. Mr Manington, may we meet tomorrow morning to discuss this? I believe your fluency in the local languages is admirable. It is essential that we include the various local Kapitans and other community leaders in this matter. We must demonstrate that no-one is above the law, be they master or servant. Land ownership must be based purely on legal documentation, not favouritism or bribery.’

‘It is a timely measure, sir,’ replied Manington. ‘Dispute over land ownership is one of the major causes of conflict on the island. There is also the matter of free land grants made to earlier settlers that have never been worked. Unscrupulous prospectors held on to these overgrown plots merely to sell them on later at exorbitantly high prices, far beyond what most honest settlers can afford. It is also high time we prepare a new map of the island – so much clearance has taken place since Home Popham’s excellent chart that it is no longer sufficient for our purposes.’

‘Perhaps our army engineers might also be involved?’ Macalister suggested. ‘Several of my officers have the surveying skills to assist.’

‘Exactly what I am talking about, captain. If we are to move forward, we must do so as one community, committed to like goals. It would be an admirable association of the military and the civilian wings. Macalister – please attend tomorrow’s meeting with Mr Manington.’ And with that sleight of hand, the gathering was back on a smooth path.

One member of the meeting had so far kept his own counsel. ‘Dr Howison? I apologise for not including you in our discussions. Yet, I observe you have been keeping close attention all the same.’ Howison had not missed a thing, his demonstrative facial expressions throughout betraying his strong opinions.

‘Do not apologise, sir! Your fruit cake was more than enough for me,’ he chuckled, sweeping a few crumbs from his lap into his palm and depositing them on a plate. The doctor was an untidy-looking fellow, his shabby clothing creased and his hair and beard untended. Like many of the medical men in Company service, he was yet another Scot.

‘I am told that after the retirement of the good Dr Hutton, you’ve been holding together the entirety of the medical provision of the island, virtually alone.’ the lieutenant-governor began. ‘The Company owes you a great debt.’

Howison seemed amused by the flattery, rubbing a hand thoughtfully through his black beard. ‘I’ve done m’ job as many others alongside me. Dr Hutton left a remarkable legacy and had trained up many orderlies to a high standard but, despite numerous requests, we are still lacking doctors. My assistant surgeon Dr Corbett – we arrived together in ’95 – died of the breakbone fever in ’98. Since then, we’ve been promised and promised – but so far nothing. Not to mention the dire state of our hospital buildings, which if I may say, are somewhat more crucial to the settlement than a grand new Government House,’ and with that he offered a baleful glance in the direction of Mr Phillips. Dr James Howison was not a man to mince words. He had already judged that Leith was a man who desired to hear the truth thus he intended to give it to him. ‘On the other hand, whilst we may have much to put right on the island, we have made astonishing progress all the same. And as Captain Macalister has already pointed out, this was done largely by private endeavour. Instead of giving me praise, if I may say so, I have a long list of other requirements that would greatly enhance the health and wellbeing of the island’s population. May I be so bold as to raise this matter bluntly, sir?’

Leith smiled back warmly. ‘You may indeed, sir. Your needs are high up on my list of urgent matters. First and foremost, we need a new hospital. The Council in Bengal has already directed me to purchase land for this self-same purpose. I appreciate that you have struggled alone for many years, but help is now at hand. I shall write immediately to request more surgeons. Be assured we are with you on this matter. Nothing is more important than our medical services!’

It had been a good meeting all in all, one that boded well for the future. Leith had proved an excellent fellow with the skills of an experienced soldier and yet the sensibilities of a seasoned administrator. If Phillips had not exactly won over the local men, Leith shared some of their reservations about him. No doubt his assistant had been thrust upon him by the Council in Bengal. As the others filed out, George Caunter lingered as requested, tapping his fork nervously against his plate, as if in time to some internal tune. He was still not entirely at ease. William Phillips also remained at the table, helping himself to another cup of tea.

Lt-Governor Leith leaned over to address him. ‘Mr Phillips, if I may? There’s no need for you to stay. I’m sure you have many things to attend to. I would like a quiet word with George – alone.’

Phillips placed down his cup with an air of wounded pride, before striding stiff-backed out of the meeting room, his displeasure so palpable that Caunter had to repress a smile. ‘Mr Phillips is very dedicated to his duty,’ commented Lt- Governor Leith wryly. ‘I hope I have not offended him, ‘he added with a twinkle in his eye.

Shuffling a few papers lying on the desk before selecting one, he raised it to his eyes as if short-sighted. ‘I read the report on your discussions with the sultan of Perak. I am impressed by your handling of these local potentates, which makes you the perfect choice for the matter I have in mind. The Governor-General has concerns about the kingdom of Queddah. If we are to raise the status of Prince of Wales Island within the region, we must address the issue of our proximity to a possibly hostile Queddah, a vulnerability which could in time rebound upon us. Whilst Queddah holds the facing coastline, we will always be prey to an enemy force using it as a base from which to attack us, whether it be local or foreign foe. Your thoughts, Mr Caunter?’

George Caunter took a deep breath, all the while anticipating what his superior might wish to hear. Leith was a soldier. Had the Company directed him to invade Queddah and absorb it as they had done with many states in India? If so, it seemed to him ill-judged. Queddah was already on its knees. But would a man like Leith prefer military action to negotiated agreements?

‘I believe we should approach the sultan with a proposition for the cession to us of a portion of the coastline. Sufficient blandishments could accompany this agreement to appease the sultan’s pride. Queddah is not in any position to object whatever we choose to do but an amicable agreement respecting the sultan’s majesty would be preferable. Such an agreement would also be a boon to their local trade and agriculture, which the sultan would recognise. We must respect that the Malays have a distinct code of etiquette in which the public saving of face is vital. Threats and posturing – even from a position of strength – might result in the very opposite result. The Malays are a proud people. But they love to bargain…’

Caunter’s hesitant suggestion was met with a wide grin. ‘Then we agree that the best stratagem is bridgebuilding, an approach of mutual interest and friendship. No military officer worth his salt would ever go to war if there was another alternative less costly both in lives and future relationships. The same applies in civilian matters, of course, perhaps even more so. Mr Caunter, I would like you to be my representative at the court of Queddah to conduct these delicate negotiations. You are known to the sultan, you understand the local sensibilities, and you have experience in this field. Dear Mr Phillips has many good qualities, but sensitivity is not one of them. Choose some local fellows to accompany you who might carry weight at the sultan’s court. The GG wants the matter wrapped up quickly, with the least fuss possible. There’s no better man for the job, Caunter. What say you?’

Leith’s proposal momentarily took his breath away. He had thought this ‘private word’ was about quite a different matter. It spoke volumes for the regard and confidence that the Company had in him – and the wisdom of the new lieutenant-governor.

‘It would be an honour, sir. I believe I am the man for the job and can guarantee the desired settlement within a few months. Queddah is in dire need these days. They would recognise the benefits if the terms were cloaked in accordance with their sense of pride and the dignity of their kingdom.’

‘Well put, sir.’ Leith paused as if about to dismiss him, before suddenly continuing. ‘By the way, Mr Caunter, there is one other issue before you take your leave. I believe your wife is expecting a child any day?’

Caunter smiled, pleased that Leith had bothered to inquire of his family. ‘Indeed, sir. But have no fear. My domestic arrangements will not interfere with my duties–’

‘–You misunderstand my meaning. Please wait until the child’s arrival and your wife is sufficiently recovered before leaving for Queddah.’ Leith stepped over to a side table and poured out two glasses of sherry.

‘I think it’s late enough in the day for a small glass, don’t you think?’ He handed one to Caunter. ‘You may have wondered why you were not considered for the position of Assistant Superintendent by the Council, given the responsibilities you have assumed so adeptly these past years. I want to assure you again that your conduct has been impeccable, and your service fully recognised. There has, however, been some concern amongst certain Council members regarding your domestic arrangements…’ Leith stopped, uncomfortable at broaching the topic, cleared his throat and rearranged his notes while Caunter chewed on his lower lip. He had been wondering when this would come up.

‘My dear wife Harriet died in childbed two years ago giving birth to our twins, Sarah and Richard. It was a personal tragedy beyond measure. Not only had I lost my dearest friend and companion, but I was left with five motherless children in this foreign land. My eldest was only seven years old. At the same time, I was dealing with the responsibilities of the administration–’

Leith raised his hand. ‘We understand how difficult it must have been–’

Caunter broke in. ‘–I would appreciate the opportunity to explain myself. I understand the concerns in Calcutta about liaisons with native women. Generally, I share the prevailing opinion. Yet sometimes it is necessary to examine an individual case on its own merits and refrain from judging purely on perceived notions. If I may continue?’ Caunter surveyed Leith with a direct gaze, neither apologetic nor embarrassed. Leith waved him on as he sipped thoughtfully on his drink.

‘Of course, I had wet nurses and servants aplenty to take care of the children’s needs –but little ones need a mother’s love. A young Eurasian Christian woman was recommended to me; she spoke good English and was from a decent church-going family. Her father is an importer of building materials and tools who has established himself as a small trader of good standing. Silvia Thomas came into my home in the role of children’s companion. Before long, my little ones grew to love her, and my babies soon knew her only as their mother. And then, Miss Silvia won my heart–’ Caunter paused, embarrassed now by his admission; he was not a man given to flowery language.

‘I believe she is a Roman Catholic?’ Leith prompted softly.

Caunter sighed. ‘She has publicly embraced the Anglican Communion now. We were married by English law.’

‘Yet, she has been observed attending mass at the Catholic chapel.’ Leith grimaced. ‘There have been letters of complaint to Council. There is always tittle-tattle, especially about those in authority. It has been suggested that this marriage affects your disposition to the locals, bringing your loyalty into question. The substantial amount of money awarded to Mrs Timmer and the inflated lease to Scott for Government House gave credence to this notion in their opinion–.’

Caunter could not help but break in to defend himself. ‘–They were monies she had been owed for several years! Superintendent MacDonald had withheld payment whilst considering the purchase of land for a new building but all along we were still occupying Light’s property! The lady has been living in difficult circumstances since the death of her husband. She is the mother of Superintendent Light’s children, legal heir to all his property. It is not a matter of favouritism but justice, sir! You yourself have just stated that it must be seen as the same for all.’

The lieutenant-governor nodded his agreement with an air of frustration. ‘Just so, sir. I do not disagree with your sentiments. Yet ambitious men exploit what they see as the perceived vulnerabilities of others. Unorthodox behaviour will always be a mark with which to beat you. George, I apologise most sincerely for having to raise these matters. If it’s any consolation, it matters not one iota to me whom a man marries should the lady be a good wife and mother. But the prevailing opinion is that the Company wants British men with British wives raising British children for the service. I raise the issue to let you know that it was this, not any failure of yours to acquit your duty, that stood against you when the appointments were decided. Rest assured I will do all in my power to make the case for you. Naturally success in Queddah will go a long way to convince them of your reliability.’

It had been an uncomfortable conclusion to an otherwise successful meeting, although Caunter respected Leith for both laying the matter on the table and offering his support. Yet, it did not change the fact that someone had informed on him in a most malicious way – nor did it justify the foul prejudice that regarded women of these parts as nothing but chattels.

‘Thank you for your honesty, Sir George,’ Caunter muttered through gritted teeth, his frustration threatening to reveal itself. ‘I appreciate that this must have been an unpleasant duty. For my part, I intend to prove myself by my own endeavour so that my loyalty will never again be in question.’

‘Good man. That’s the spirit. Find a way or make one for yourself. In the end each man is responsible for his own destiny. I do not intend to re-visit this topic again. The matter is closed. I wish you and your wife all the very best for the coming birth.’

There was much on George Caunter’s mind that afternoon as he made his way homeward, his thoughts a roiling tempest of opportunities granted, stratagems planned, and revenge sought. Who had informed on him? Ambition lay in every breast. He trusted no one.