Part Five: Britain and Ireland

Sarah Lennox was born into one of the great families of England, the youngest surviving daughter of Charles 2nd Duke of Richmond and his wife, Sarah Cadogan, a society heiress and great beauty. The family home was the great estate of Goodwood in West Sussex. Both parents died young, however, leaving their only son Charles as 3rd Duke of Richmond at the age of sixteen. Sarah’s eldest sister Caroline had earlier eloped with the Whig politician Henry Fox and had been cut off by her parents, so in 1752 Sarah and her sisters, Louisa and Cecilia, were sent to Ireland to be raised by her older married sister Emily, the Duchess of Leinster.

Emily Lennox Fitzgerald was a remarkable woman herself who was eventually to cause a scandal. After giving birth to 19 children (11 who survived infancy), she had an illegitimate child to the much younger William Ogilvie, her children’s tutor. On the death of her husband, the Duke of Leinster, in 1774, Emily married Ogilvie - and went on to have four more children to him! It was quite the society scandal of the day.

Sarah also grew up to be an independent, strong willed young woman. At the age of 13 she returned to London to stay with her eldest sister Caroline Fox in whose company she was presented at court in 1760. Such was her beauty and charm that she caught the eye of the Prince of Wales (soon to be King George III) who was completely entranced by her and wished to make her his wife, but his advisors disapproved of Sarah as a future queen; she was instead chosen as a bridegroom at his wedding to Princess Charlotte of Mecklenburg. With little say in the matter – and to keep her away from the young king, Sarah was soon married off to a suitable baronet, Charles Bunbury. She was unhappy in her situation and actively rebelled against it, having an affair with Lord William Gordon that resulted in an illegitimate child, Louisa Bunbury, born in 1768. Not long after the birth, Sarah and William eloped together, causing a furore in both families and becoming the cause célebre of the day. Bunbury eventually filed Parliament for a divorce, a highly unusual and scandalous matter at the time. Sarah’s reputation was entirely ruined when it was granted in 1776.

Sarah and Gordon spent the intervening years together, mostly in his native Scotland, but his fortune was small and Sarah’s extravagance and outrageous behaviour eventually destroyed their affections for each other, causing him to abandon her. She and her daughter were forced to take refuge at Goodwood with her brother, Charles,3rd Duke of Richmond, in social disgrace. Whilst in Ireland to visit her sisters Emily and Louise, Sarah met an Anglo-Irish army officer, Col. George Napier (1751-1804); they both e fell madly in love. Napier was an unlikely choice for the once glittering socialite; he was a courageous but humble military man who had no interest in the limelight with no fortune other than his army pay to sustain them.

Together, however, they enjoyed the happiest of marriages, one that produced a number of outstanding children, most notably Charles, Emily, George, William, Richard, and Edward. Sarah seemed completely content in her new life of domesticity and genteel poverty, having finally found the peace her former life of luxury and indulgence had denied her.

After a few years of struggling to make ends meet, moving from the charity of one family member to another without a place to call their own, George was appointed Comptroller of Accounts in Ireland with a regular annuity. At last they managed to buy their own property, a small manor house, Oakley Park, in Celbridge, Co Kildare, on the fringes of her sister Louisa Connolly’s expansive Castletown estate. There the Napiers raised their family in no nonsense fashion, sending them to the local school for their education. They lived there until George Napier’s death in 1804. Sarah sold the property and moved back to London to ensure her children made the most of their connections, because they did not have great wealth behind them. Purchasing a house on Cadogan Place, she lived there with her children and their families until her death in 1826 at the grand old age of 81, surrounded by her beloved family, still a feisty woman to the last.

Sarah Lennox Napier (1745-1826

The young Lady Sarah Lennox c. 1760

Lady Sarah Lennox c. 1762 by Joshua Reynolds

Lady Sarah Bunbury c.1765 by Joshua Reynolds

The Honourable Colonel George Napier

Oakley Park, Celbridge, Co Kildare c. 1900

[Photo credit; Robert French]

Lady Sarah Napier in old age from a later aquatint by Walker and Cockerell

The Pérois family

César Auguste Pérois was a native of Paris, the son of a prosperous wine merchant. His family were royalists and opposed to the Revolution. Young César, still only eighteen joined the emigré opposition led by Monsieur (the younger brother of Louis XVI), his first experience as a soldier. By 1792, when the Revolution abolished the monarchy, all the emigrés were declared traitors. It was impossible for Pérois to return to Paris.

Initially, he took refuge in the Netherlands but when the old Dutch Republic fell in 1795 and a pro-French Batavian Republic was declared, he was forced to flee again. The next we hear of M. Pérois is in 1796 at the port of Hull, Yorkshire, probably in desperate circumstances and in need of a job. Pérois had always been an accomplished musician and with this exceptional skill, he managed to find employment in the most unlikely of places. He joined the Regiment of the York Fencibles as it band master, serving with them for the next six years.

In 1798, his regiment was transferred to Ireland during the rebellion of Wolf Tone (who received military aid from the French Republic). Pérois and his regiment were stationed in Londonderry ( or Derry as it is known to the Irish). When the regiment was disbanded two years later, he decided he was done with the military life. Pérois had already settled down with a local girl and had at least one child by then. It was time for him to make a life in his adopted country.

Londonderry was by this time a British settlement, famed for its stout walls, the centre of British rule in Ulster, which had been a notorious thorn in Britain’s side of late. Settlers from all over Britain, especially Scotland, had been encouraged to outnumber the troublesome local Irish. Since then Londonderry had become a thriving town, eager to expand and establish itself with the trappings of decent British society. Pérois set himself up as a teacher of music and dance, a tutor to the up and coming middle class and newly prosperous citizen,s as well as to the local aristocracy and the families of the military officers.

His school became popular both with the British - for he was a Frenchman who had fought against the Republic– and also with the Irish, because he was a Catholic and had married an Irish woman. His pupils came from all parts of Donegal, Tyrone and Londonderry.

Little is known of his wife, Madame Pérois, other than her name: she was born Mary Ann Hegarty (1778-1826), an Irish woman presumably of Derry. Together the couple lived on Bishop Street with at least six living children: Emily Frances (1800-52), Miss E. Perois (1804-1822), John Henry (1810-?), Mary Rosetta (1812-?), Frederick Claude (1816-48) and Julia Matilda (1819-1856).

Mary Ann died in March 1826. Some years later, in 1834, Pérois took a second wife, Mrs Marianne Josephine Adamson of Dublin – who may have been of French origin herself. A year earlier the same Mrs Adamson had opened a school on Bishop Street, the street on which Pérois lived. Perhaps it was even the same premises, used as a school now that all the children had grown up and left. In 1835, a baby boy was born to them, Louis Pérois. Sadly his father, César, died only two years’ later, on May 10th 1837, after which mother and son returned to France.

César Pérois’ obituary appeared in the Derry Journal on 18th May 1837. It is obvious that M. Pérois was a much respected and admired member of the local community.

César Auguste Pérois (c. 1773- 1837)

A typical British regimental band led by the bandmaster c. 1800

The Dance Lesson by Cruikshank

“ Sacred To the memory of

CAESAR AUGUSTE PEROIS

of this city who died May 10th 1837

aged 64 years.

Also of MARY his beloved wife

who died March 18th 1826 aged 49 years And eight of their children.”

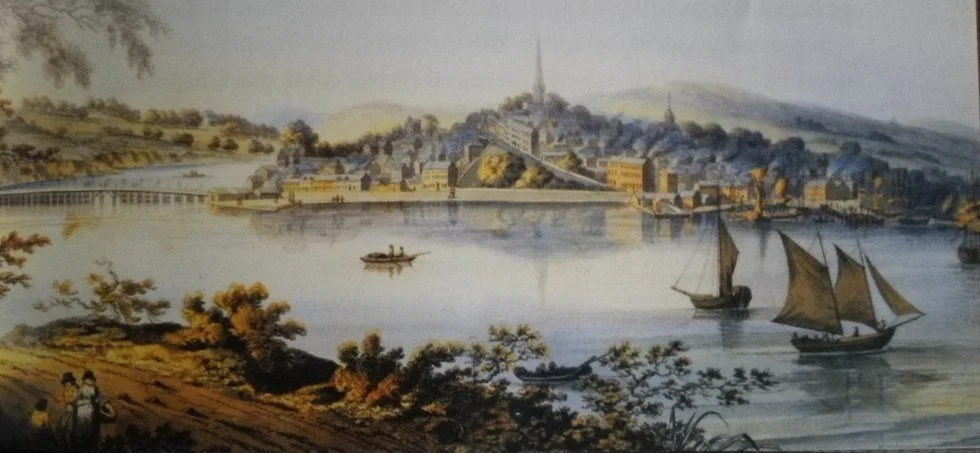

Derry in 1800s

[Picture credit: emmafcownie.com taken from Discover Derry by Brian Lacey]

“M. Perois was so universally known and esteemed, in this city and its neighbourhood, that it would be almost superfluous to say a word with regard to his character. In his professional capacity, he united talents of the first order to a liberality of feeling, raised far above the petty jealousies too common amongst professional people. His numerous pupils and friends will long remember with pleasure and regret that brilliant flow of spirits, and that ease and correctness of manner, which render him an acquisition to every society of which he formed a part.”

The Perois sisters

Miss E Perois (c.1804-1822

Miss E Perois is fated to remain an enigma. The only real evidence we have of her existence is the announcement of her marriage to William Light on 24th May 1821 in a newspaper, and a brief outline of her father’s life taken from his own obituary. We do not even know the date of her death, other than it is likely to have occurred in 1822, for by the beginning of 1823, William Light had left Ireland for good and there is no further mention of his wife from then on.

Later in his life, William Light corresponded with his friend Charles Napier after the death of his beloved wife, probably sending his condolences. In Napier’s reply, he refers to William ‘understanding’ his grief after losing the one that meant so much to him. This can only mean E Perois; Napier would never have referred to the breakdown on Light’s second marriage in those terms. This points to Light’s first marriage being a love match and the death of his wife a bitter tragedy, perhaps from which he never quite recovered.

We do not know what the first Mrs Light died of although many possibilities for premature death are possible in the early nineteenth century: the ubiquitous tuberculosis, smallpox, cholera, scarlet fever and so on, not to mention the most frequent cause of female mortality: childbirth. When a young woman passed away in the early years of her marriage, death in childbirth was always the most common reason.

Amongst Light’s private papers, one unusual sketch has been found. It is literally a preliminary sketch, no more than an outline on paper but enough to show a young woman holding a baby close to her. Her hair is knotted in a bun and she is wearing a waisted full-length dress, with the hint of a cloth over her shoulder. The baby is staring directly at the artist, but its features are suggested rather than penciled in any detail. This sheet of paper was retained amongst his possession, those salvaged from the fire in Adelaide that destroyed much of his written and artistic record. It must have meant something to him, although as a piece of art is almost childish in its simplicity. William Light painted scenery, ancient monuments, boats, detailed self portraits ; this is completely different to his usual work.

Is it a daydream, a wish for the life he might have had if his beloved bride had survived the birth of their child? Or is it a memory of his own mother holding his baby brother long ago, when he was a child before he was sent away to England? Both women died in 1822; after then William Light spent several years aimlessly wandering Europe or fighting a reckless campaign for a hopeless cause, suggesting he was struggling to come to terms with his life. From these scant pieces of evidence, Legacy has tried to create an authentic story for E Perois. It may not be based on historical evidence but is an attempt to give a voice to a woman who mattered very much to William Light and deserves to be given a voice.

Freeman’s Journal of Derry June 6th 1821

My apologies for the poor copy. This is taken from a photograph of the original sketch, part of the William Light Collection in the Art Gallery of South Australia (Adelaide).

The collection is no longer on public display and can only be visited on prior arrangement.

My thanks to Jennifer Light for this image

Although we have so little information about her younger sister, oddly enough much more is known about the eldest of the family, Emily Frances, known affectionately as Fannie. A portrait of her exists, which is an exciting addition to our knowledge of the Pérois family. It is also tempting to wonder if perhaps the two sisters were in any way alike.

Fannie Pérois first enters the historical record in 1837 when she married Archibald Stewart (1784-1866) who appears to have been an illegitimate son of Lord Robert Stewart, 1st Marquess of Londonderry. They were married at Greyabbey, which is only 2 miles from Mount Stewart, the family seat of the Stewart family on the east of Strangford Lough. Archibald Stewart was thus half brother to the 2nd Marquess, Viscount Castlereagh a leading politician and Foreign Minister of the period.

What had brought Fannie Pérois from the streets of Londonderry to association with one of the great families of the British settlement? One can only conjecture. Like her father, Fannie was probably an accomplished musician and teacher. The family of Lord Robert Stewart was large (he had 12 living children from his two legal marriages) so perhaps Fannie first arrived at Mount Stewart as a nanny or governess. The original sketch by George Dance is dated June 1816, suggesting Fannie may have resided at Mount Stewart for some years before her marriage.

Nevertheless, Fannie had done well for herself in the unforgiving social climate of the day. Now Mrs Archibald Stewart, Emily Frances went on to have two children: Augustus John Stewart (named for his maternal grandfather) and Sarah Frances Stewart.

Miss Emily Frances Perois (1800-1852)

Mdlle Fannie Pérois copied in pencil by J. F. Odell in 1880

The sketch reads ‘Mount Stewart, June 12th 1816’ by G. Dance

[Picture Credit: V and A Collection]

Mount Stewart House, Greyabbey, Co Down

[Picture Credit: Wikipedia Commons; Ulsterbeef]