Part Four: Java

Olivia Mariamne Raffles (1771-1814)

Born in Madras, the daughter of George (or Gregory) Devenish and his beautiful Circassian mistress, Olivia was sent back to her father’s family in Roscommon, Ireland at a young age. which explained Olivia’s dusky colouring. At that time ‘Circassian’ had become something of a byword for exotic beauty and often implied mixed heritage. It is entirely possible that her mother had in fact been Indian, which may explain Olivia’s dusky beauty.

Olivia was a dark, willowy beauty with a wild headstrong personality. At only 14 years old, she took up with a 34 year-old Scottish mariner, Captain Jack Hamilton Dempster, when his ship, the Rose, was detained by customs in Cork in 1785, an affair which resulted in the birth of a daughter, Harriet the following year. One can only imagine the scandal this caused. Dempster returned to London where he married a Miss Jean Fergusson but he took responsibility for the child who was raised in Scotland by the Dempster’s family.

The affair appears to have continued, however. In 1792, Olivia, now 21, took passage back to India on Dempster’s ship Rose where they are said to have resumed their relationship. Yet three months after her arrival in Madras, Olivia married Joseph Cassivelaun Fancourt, a Company surgeon. The marriage appears to have been unhappy. It produced no children and by 1798 Olivia was living in London with two servants, her husband remaining in India. It was rumoured she took up again around this time with Dempster after his wife died.

In 1800 Olivia’s absent husband Fancourt died of fever. In the same year Dempster was lost in the South China Sea in the sinking of the Earl Talbot. Although Olivia’s circumstances were now much reduced, her beauty and vivacity had made her society’s darling . She was feted by many admirers, including the young Irish poet Thomas Moore who wrote several poems about her. She may well have been his mistress. Her family were very concerned about her reputation, which continued to be troubled by scandal.

In late 1804, Olivia Fancourt made a visit to East India House on Leadenhall Street about her widow’s pension. It seems this is where she first came in contact with young Thomas Stamford Raffles who was more than ten years’ her junior. In circumstances that are still unclear, Raffles and Olivia married in March 1805 just before their departure for Prince of Wales Island and his new appointment. Olivia must have had some contact with her daughter before they left, for they both had miniatures painted as mementoes.

Both on the sea journey over and the island itself, Olivia quickly gathered a coterie of admirers about her. The orientalist John Leyden who stayed with the couple for a few months became besotted with her. Yet Raffles did not seem to be troubled by the attention she received from other men; on the contrary he appeared to revel in it. Together Mr and Mrs Raffles hosted many social occasions at the house they built on the island, Runnymede, Olivia enjoying her position as the most fêted lady on Prince of Wales Island. But all was not well. Olivia’s health was poor and she was often confined to bed with a variety of affliction: amoebic dysentry and malaria, very common in the Indies as well as liver disease, possibly hepatitis. There were, however, rumours of her excessive alcohol consumption; her giddy public displays at parties and dinners suggesting that she was overly fond of wine.

In 1811, Olivia accompanied the army on the Java Expedition, where she again charmed all the gentlemen, particularly the Governor General Lord Minto. After Java was occupied and Raffles appointed Lieutenant-Governor, the Raffles settled at the governor’s palace at Buitenzorg outside Batavia where they lived in splendour. But Olivia continued to suffer from increasingly serious liver problems until she died in 1814, aged only 43. Raffles was devastated by her loss. She was buried in Tanah Abang Cemetery in Batavia, although a poignant memorial to her was erected by Raffles in the grounds of Buitenzorg.

Miniature of Olivia Raffles (1805)

by Nathaniel Plimmer

The Palace of Buitenzorg, Java by Willem Troost (before 1834)

[Photo credit: Rijksmuseum Collection]

Olivia’s memorial in the grounds of Buitenzorg, now the Botanical Gardens at Bogor, Java

“Oh Thou Whom Ne’er My Constant Heart One Moment Hath Forgot,

Tho’ Fate Severe Hath Bid Us Part,

Yet Still Forget Me Not”

Born to a naval captain (who was over fond of drink and gambling) aboard ship off Jamaica, young Thomas Raffles grew up in an unhappy household struggling to make ends meet because of the proclivities of Raffles Senior. By the age of 13, Thomas was forced to leave school to support the impoverished family. His maternal uncle, a tea trader, secured him a position as a clerk at the headquarters of the East India Company, a particularly lowly paid and humdrum existence. By night, however, Thomas continued his studies alone at home and by day he knuckled down to the tedious administrative tasks, determined to be the best he could in order to impress his masters.

By the late 1790s, Raffles was now the sole provider for his mother and sisters, the family now estranged from their father. Through a combination of hard work, natural talent and the cultivation of Company men of influence, began to rise through the ranks, ultimately achieving the near impossible for a young man of his humble station– an overseas posting. Raffles had made the first of several leaps up the ladder. He was now Assistant Secretary to Prince of Wales Island, part of a new administration there now that the island had been raised to the status of Fourth Presidency of India.

Raffles and his fascinating wife Olivia, who made an unlikely pair, were quick to make their mark in island society, helped by Raffles’ insatiable drive. He learnt Malay and immersed himself in studying the East as well as making himself indispensable to the administration by his phenomenal work effort. All this while struggling with ill health which plagued both Raffles and his wife.

In 1807, after a bout of malaria, Raffles travelled to Malacca (temporarily in British hands due to the French occupation of the Kingdom of the Netherlands) to convalesce as the guest of the Resident, Captain William Farquhar, an experienced Company Officer. From him, Raffles learned about Farquhar’s suggestions for Malacca and his belief that the British should launch an attempt to wrest Java from the French. When he returned to Penang, he wrote a report to the Governor General, Lord Minto, outlining what were in fact Farquhar’s proposals but refraining to mention his name. Thus began a lifelong enmity between the two men, made even worse when Raffles was appointed ‘Agent to the Malay States’ in 1810, tasked with planning the Java Expedition over Farquhar’s head.

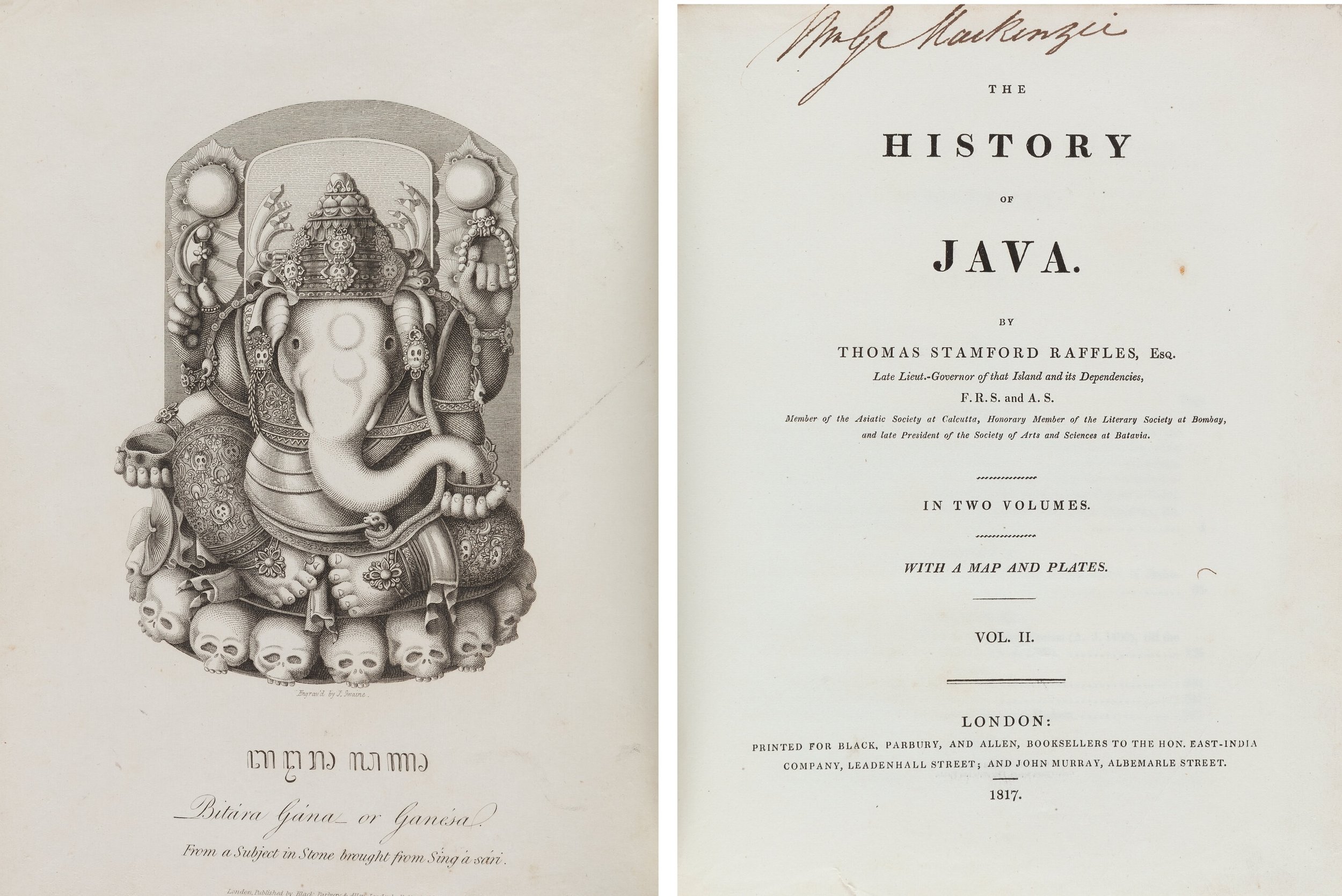

From 1811-16, Raffles was Lt. Governor of Java, a period that is featured in the novel in some detail. When he was eventually dismissed –under a cloud of accusations of corruption and mismanagement– he returned to England and used his home leave not only to marry a new wife, Sophia, but also to publicise a book he had written The History of Java. With his unfailing skill at networking, he managed to win the favour of Princess Charlotte, the daughter of the Prince of Wales who knighted him. In 1818, the Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles received a new appointment: Governor of Bencoolen, a forlorn, disease-ridden posting, the only British post in Sumatra. It was a step down from Java but he was back in the game.

On a visit to Penang, where Sophia was to give birth to their second child, Raffles joined an expedition with Farquhar to survey the swampy little island of Temasek at the tip of the Malay Peninsula as a possible new British enclave. Exploiting local rivalries for the throne of Johore, Raffles again undermined Farquhar and managed to obtain Temasek - Singapore– from under his nose. The rest, of course, is history.

Surprisingly to most people, Raffles did not spend much time on the new settlement of Singapore, leaving William Farquhar as Superintendent to do the hard work while he returned to Bencoolen, dropping in from time to time, and generally disapproving of most of Farquhar’s decisions. believing that Farquhar was too inclined to favouritism to the Malays and Chinese. In 1823, matters came to a head between the two men. Raffles sacked Farquhar abruptly, appointing his old friend John Crawfurd as the new Superintendent.

But by then both Sophia and Thomas were suffering from extremely poor health. Sophia had given birth to four children, only one of whom had survived Bencoolen, Ella who had already been sent back to England. They decided they must return to England and in 1824, they set out on the Fame, carrying with them all their worldly possession, a huge collection of irreplaceable cultural treasures. The ship caught fire just off Sumatra; they were lucky to escape on one of the life boats, but lost everything. Finally, almost broken by events, Raffles and Sophia reached England in August 1824 to find that Britain and The Netherlands had made peace; Bencoolen was ceded to the Dutch and Singapore-Malacca-Penang, the Straits Settlement were now to become the most important British holding of the era.

Singapore was to ultimately make his name, yet Raffles himself did not benefit from it at the time. Riddled with debt, plagued by failing health, broken by the loss of his children, Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles died of a possibly brain haemorrhage on 5th July 1826 at the age of 45. It was left to his devoted wife, Sophia, to keep his memory alive. She wrote a memoir of his life and achievements, in which she sidelined Olivia, Farquhar and others, managing to set the Raffles ‘legend’ in the public eye. After her death in 1858, 800 items of the Raffles Collection (brought home in 1816 after his stint in Java) were presented to the British Museum.

Thomas Stamford Bingley Raffles (1781-1826)

Sir Thomas Stamford Bingley Raffles 1817

by George Francis Joseph

[National Portrait Gallery, London]

Wedding portrait of Sophia Hull Raffles (1786-1858), 2nd wife of Raffles, and mother of 5 children, four of whom died in infancy 1821-3

[copy of original by A.R. Chalon 1817]

Frontispiece of The History of Java Vol II by Raffles 1817

[Credit: Heritage Auctions HA.com]

Wayang Kulit figure: Trigannga, son of Hanuman from the Ramayana

[Photo credit: The British Museum Raffles Collection]

Statue of Raffles Westminster Abbey ( Sir Francis Chantry 1832)

[Photo Credit: Dean and Chapter, Westminster]

Hugh Robert Rollo Gillespie (1766-1814)

The biography of career soldier, Rollo Gillespie is so full of incident and adventure that it reads more like a novel. Gillespie is something of an enigma; regarded as either a dangerous renegade or a great hero. It is entirely likely that he was something of both.

Born of Scottish landed gentry in Co. Down, Ireland,, young Gillespie, a slender lad with red-gold curls was thoroughly indulged by his father, who called him ‘a delicate boy’, despite his wild behaviour. Sent to England for schooling, Rollo proved thoroughly resistant to learning and was constantly in trouble, his only ambition to be a soldier. Thus, at the age of seventeen, he joined the army, as a Cornet in the 3rd Irish Horse Guards.

His private life was eventful. In 1786, aged twenty, he eloped to Dublin with a Miss Annabell Taylor of Co. Tyrone against the wishes of both families. There they married and had a son, another Rollo but the marriage did not last. Gillespie indeed never married again but kept a string of mistresses with whom he fathered a number of illegitimate children. The following year, 1787, Gillespie became embroiled in a dispute with a local squire known as ‘Mad’ William Barrington. It culminated in a duel in which he shot Barrington dead. A warrant was duly sent out for Gillespie’s arrest but he went on the run for a few months until he eventually tired of his situation and surrendered. Somehow he was acquitted, on the unlikely grounds of ‘justifiable homicide’. Luck (probably assisted by good connections) followed him as much as mayhem, it would seem.

Gillespie’s first major overseas posting was to the West Indies where he spent the next ten years, mostly in St Domingue (Haiti) fighting against the French. His daring raids are reminiscent of swashbuckling pirate stories. During this period he almost died of yellow fever and was seriously injured several times, always managing to bounce back to health - so much for the ‘delicate boy’.

During one trip home on leave, Gillespie again managed to have a run in with the police. He attended a theatre performance in Cork where he took umbrage at a fellow member of the audience, (probably an Irishman) who did not stand for the national anthem. Gillespie pulled him to his feet – and broke his nose. A warrant for his arrest was sent out but our wily officer escaped, this time dressed as a woman with a borrowed baby to complete his disguise!

Back in the West Indies, Gillespie returned home one evening to find thieves ransacking his quarters- he killed six men and the remaining took to their heels. Yet for all the mayhem and drunken disorderly behaviour which characterise his life, as an officer Gillespie was impeccable. His regiment in the West Indies (the 20th Light Dragoons) was regarded as the best in the army - and the happiest. Major Gillespie was known to ensure that his men were well fed, clothed, sheltered and given good medical care. He led every action from the front and was adored by his men. Gillespie was truly a soldier’s officer.

On his return to England - in debt and barely escaping a prison sentence for fraud, Gillespie took service in India, given the command of the 19th Light Dragoons based in Arcot near Madras. Unusually, he chose the overland route to India rather than going entirely by sea, a unique Grand Tour all of his own. Naturally it was to be an eventful journey. In Poland he ran foul of a Russian general, losing all his guns and almost his life. He fought off pirates on the Black Sea. In a sword fight in Constantinople he injured a French officer. Crossing the desert he was taken by bandits who released him only after he managed to cure their leader’s raging headache! The final stage of his Odyssey was by dhow through the Arabian Gulf to Bombay and then trekking across the Deccan to Madras. Whilst stationed at Arcot, Gillespie was involved in the Vellore Mutiny, s described in Legacy Chapter 12: Palmacottah. There were those, like Major Welsh in this chapter, who thought Gillespie a dangerous loose cannon, but others (including the Governor of Madras) regarded him as ‘the bravest soldier in the army.’ Major Rollo Gillespie confounded all attempts to define him.

Part Four of Legacy covers Gillespie’s Java adventures in some detail. As second-in-command of Lord Minto’s expeditionary force under the former American General Samuel Auchmuty (who had fought for the British in the War of Independence), Major Rollo Gillespie was front and centre in the actions against the Dutch forces of the pro-French General Janssen. It was Gillespie’s military genius that led to the successful capture of Fort Cornelis and the collapse of the Dutch government in Java. Gillespie led the final assault whilst suffering from malaria and having survived poisoning (administered at breakfast that day by his Dutch cook in his morning coffee). During the assault, Gillespie was also badly wounded and fainted, falling off his horse. He was resuscitated by the field ambulance and then jumped back on his mount to re-join the fray. In the aftermath of victory, Gillespie spent many weeks in hospital recovering from his many injuries, during which time Stamford Raffles established himself in the administration and became Lt. Governor. The two men were always at odds, ultimately bitter rivals and enemies.

After Gillespie’s successful campaign in Sumatra against the Sultan of Palembang, he returned to service in India, determined to bring charges of incompetence and corruption against Raffles, in alliance with other disgruntled former associates of the controversial Lieutenant-Governor. Whilst visiting Bangalore – never one to miss an opportunity for reckless adventure– Gillespie singlehandedly stalked and shot a rogue tiger who had been roaming around the racing course and causing great distress.

Raffles was subsequently dismissed from his post in Java, but Gillespie himself did not live to enjoy his revenge. In 1814, whilst fighting in at Khalanga Nepal, Major-General Gillespie was shot dead leading another spirited attack against the hill fort of Nalapani, as usual from the front. Gillespie was knighted posthumously for his services to the British army. A commemorative statue to Gillespie stands in St. Paul’s Cathedral like his old rival Raffles!

The young Rollo Gillespie c. 1785

Gillespie by William Haines

“A more dazzling career than his, there is not in the whole annals of the regiment”

Major-General Gillespie by Emily Hawkins

Major General Robert Rollo Gillespie

by Robert Home

The Death of Gillespie by James Grant

[Cassells Illustrated History of Indian by G T Thompson]

Major-General Sir Robert Rollo Gillespie by Sir Francis Chantrey (1826)

[Photo Credit: 14GTR Wikipedia]