India: On The March

William Light was an inveterate diarist who kept journals throughout his life, most of which were lost in the fire in his Adelaide home in 1839. The chapter ‘On The March’ is actually based upon the published India journals of Light’s brother-in-law Major James Welsh, describing a great trek he led down the length of India from Poona to the Carnatic with his regiment to take up a new posting in 1805. It is thought William Light accompanied him on this journey as a civilian observer and that the experience may have played a part in his subsequent decision to enlist in the British army. In the absence of William’s own diary and sketches–which he would definitely have produced on such an expedition – I recreated this journey ‘in his own words’ in this chapter. In the end we decided it was surplus to requirements, but I include it here as a fascinating colonial British insight on the vastness of India and its people.

The Gokak Falls Karnatika early 19th C.

[unknown artist. From www.mutual art.com]

Sarus ‘Demoiselle’ cranes in flight, Hurryhur

[Photo credit: www.sarusnaturesociety.com]

Bababoondungiri in the Western Ghats

[photo credit: Bynekaadu.com]

Extracts from the journal of Lt. William Julian Light. December 1805–March 1806

1st January,1806 (100 miles from Poona)

On an ink dark night pierced only by the silvery glimmer of stars, we gathered around the campfire on the banks of the river Yerala passing round a Highland whisky carried like precious cargo in James Welsh’s saddle bag. No Scotsman would countenance Hogmanay without a bottle of its finest. Far away from the bitter chill of a Hibernian winter, a company of soldiers raised the toast amid a foreign wilderness. Where I should be well upon my journey home, the greatest challenge yet now lies before me.

I had intended a short farewell visit with Sarah, delivering letters from the family. It was an opportunity to appraise her in person of all that had happened in Calcutta and Penang in the months since last we met. But my brother-in-law had other plans for me. Fully recovered now from his fever, although still prone to milder attacks, he had received new orders: battalion commander at Bellary, a fort of the southern Deccan. Separation now beckoned for the family once more but my sister met the challenge with the fortitude that comes from long experience as a soldier’s wife.

James invited me to accompany the battalion on its long march south. What better way of testing my suitability for the soldier’s life than a rigorous expedition? I could think of no better experience for it also afforded me an ideal opportunity to indulge my great passion, that of the artist. Imagine the grandeur of the mountains of India to be captured on my sketchpad! This journal has already been much neglected of late in preference to brush and pencil. James Welsh, a seasoned surveyor and talented artist himself, has been instructing me in the finer points of both landscape painting and surveying in preparation for our expedition. How fortunate I am in my brother-in-law!

On this singular night, with the coming year yet as blank as my virgin page, I am in my natural element: pen in hand, glass by my side, perched on a rock over a mighty river gorge framed by mountains, a world away from the machinations and complexities of life. This surely is my true calling. Only the raw skin chafing my buttocks and thighs from days of hard riding intrudes on my state of happiness. But they will heal and harden, as shall I.

January 9th 1806 Gokak Falls (200 miles from Poona)

Yesterday we reached the falls, an impressive cascade on the Ghatapraha river. After so long in the wilds, Captain Wakefield, commander of nearby Goreggery Fort extended us a welcome invitation to spend a few days. A charpoy bed by night and the natural beauty of this region by day are the sweetest of simple pleasures.

Today James and I spent rambling at Gokak with other officers whilst our men rested their weary bodies. The sepoys do not enjoy the relative ease of horseback as do the officers. The scenic horseshoe falls at Gokak have been carved by time from sandstone cliffs on a rocky stretch of the Ghataprata . The Cyclopaean cliff walls have been dramatically breached by several cascades formed by the diversion of the flow around the massive boulders along the upper reach. The waters plunge in a churning frenzy of mist and foam to reform below as one great river and resume their serene journey on to the sea.

It is still January and the weather is dry. By the rainy season, I am reliably informed, these falls merge into one single mighty torrent of inestimable power. It is hard to imagine anything beyond what is already there; the other must be is a breathtaking sight indeed. As a result of these singularly extreme conditions–from extreme dry heat to torrential deluge, the area is sparse of foliage, even barren in places, accentuating the rocky naked magnificence of the place. Its views are incomparable. Whilst rambling we came upon an ancient fort, several ruined temples, and a curious giant figure carved from stone, all long abandoned. How tempting to linger here in contemplation of forgotten kingdoms long fallen into decay and lost to memory! But I am a soldier now. Duty calls me on.

January 25th The Fort of Hurryhur (200 miles from Gokak)

Three weeks now on the march, nights spent in dead exhaustion rolled up in blankets beneath the stars. The days are long, past endless villages all much the same to our eyes as if caught in an unending circle. But still the road leads relentlessly south. The only break from this monotony has been when here and there we have stopped at busier settlements to stock up on supplies in bustling bazaars or to parley with native chiefs. Local intelligence on the current state of these territories is essential. One chief offered a substantial bribe if we deployed the battalion against his neighbour. It served as a timely reminder that these lands are now quite lawless; the defeat of their Maratha lords has left a vacancy that others desire to fill. With as much delicacy as possible, Captain Welsh declined. We moved swiftly on, heading for the Tunghabhadra river where the southern and eastern routes meet.

In the stout clay fortress of Hurryhur, we decided to rest a while. Captain Welsh is suffering another bout of fever. On our approach across the north bank of the river, we came upon a vast flock of Sarus birds, known as ‘Demoiselles’ for their distinctive cry, akin to the piercing sound of a lady in extreme distress. The sarus is a beautiful sight. A tall stately crane with feathers of dove grey, its neck is ringed in a band of ruby red and its head crowned in black. A most elegant creature, a demoiselle indeed.

Captain Welsh recognised the opportunity for some sport to entertain his jaded troops. With a small party of riflemen, we stalked the birds as they flocked on the south bank. No sooner were they aware of our presence, however, than they rose up in unison like a living cloud, beating their large wings and screeching their lament before soaring high above us out of reach. Out of perhaps fifty in number, we brought down only two – one of which escaped. Our hapless antics caused great amusement amongst the troops ranged along the ban shouting exhortations at us, the din no doubt contributing to our lack of success.

Welsh motioned Captain Pepper and a havildar to wade in and pluck the two fallen birds, without understanding the true depth of the water. For some moments, silence reigned when we perceived that the men were in imminent danger of being swept away. Fortunately both proved strong swimmers, dragging themselves to safety in the shallows, supporting each other and clinging to the one bird they managed to retrieve. James Welsh blamed himself for not accompanying them; they might have died in this foolish enterprise. Only his poor health had prevented him from carrying out the duty himself but, despite his raging fever, he still he took responsibility. Such is the mark of the man. That evening as guests of Captain Gibson of the 10th, we had reason to celebrate our good fortune. The bird was excellent. Although it has the appearance of a stork, it tastes much like turkey. It was very good eating, particularly after our recent deprivations.

It is well we lingered at the fort, for a messenger arrived today bringing fresh orders. Instead of Bellary, we now face an even longer journey. Captain Welsh is ordered instead to take command at Palmacottah, a small fort on the southern tip of the Carnatic, well-known to him from his earlier years in India. We are destined for another month or two upon the road. James suggests I might wish to return with the rider to Goa, from whence I might sail to Bombay for my passage for home, having already given sufficient time to this endeavour. I will hear nothing of it; I am more keen than ever to see this adventure through. Little waits on me in England and this is a supreme adventure!.

30th January Bababoodun (50 miles from Fort Harihar)

A curious event has taken place near our encampment at Bookamboody, an area of verdant beauty, wild but glorious, surrounded by three hills whose velvet slopes are charmingly clad in green. Our sepoys, both Mussulmen and Hindoo alike, are greatly excited by the location for close by is a sacred shrine, a holy place for both religions. A deputation approached Captain Welsh for leave to visit a saint who lives there in order to receive his blessing.

After weeks of hard marching, James Welsh looked with favour on this request. The men deserve a reward, and this seemed harmless enough, costing nothing but reaping much goodwill. Thus, he has given permission for any soldier to make his way up the sacred mountain, Bababoondungiri, where the sufi priest dwells. The men are instructed to rendezvous with the main battalion three days’ hence along the road. All our Mussulmen have taken the opportunity and a number of Hindus, too– almost half the entire battalion. In addition, one Christian was numbered amongst their ranks. for I myself was greatly curious to discover what was there..

As we followed the winding trail up to the caves where our saintly hermit lives, we were afforded magnificent views of the western Ghats dominating the plains of rolling green. On tiered plateaux, we came upon small plots of coffee trees, an unexpected crop in these parts. Striking up a conversation with Havildar Rajoosamy (the very hero from the river) who speaks some English, he explained the legend of this place, although I cannot vouch for his version. The Mohammedans likely have their own story.

The cave was once home to a Hindu ascetic, an incarnation of the Trimurti, the trinity of Brahma, Vishnu and Shiva combined. For centuries he had dwelled there without sustenance, living only on nourishment of the contemplation of the divine. Hindus have always visited this place for blessings or to ask for mercies. Rajoo himself wished to give thanks on account of having been spared from drowning. Yet his story did not reveal why every Musselman amongst us was on the same path. Surely reverence to Hindu deities is forbidden to them?

It was only when we finally reached the trio of caves at the summit that an answer was revealed, although not everything that transpired was plain to me. A hermit does indeed live there, a wizened toothless Moslem priest clad in a stained white cloth, who seemed not in the least surprised at the sudden arrival of a large throng of soldiers. His miraculous survival for centuries was somewhat explained; the offerings of fruit and rice, fresh milk and coconuts that were laid at his feet may well have played a part. Yet in his defence, he never consumed a thing, at least not in our presence.

From my perch at a distance on a higher rock, I observed the men making their obeisances to the saint, laying their offerings before him, and receiving his blessings. After that, the men settled down to listen, crosslegged on the rough earth. What followed appeared to be a sermon of unexpected passion, inciting the men to such an extent that they raised raucous shouts and cheers. At other times, the holy man lapsed into quiet prayerful moments when the men also fell into silent contemplation. I am always discomforted when unable to construe the language of others, for lack of understanding inevitably drives men apart, causing suspicion to arise. Although recently I have acquired a smattering of Hindi and Bengali, these men were Tamil speakers. I understood not a word. The entire episode awoke in me an ominous sense of unease that I could not shake.

Returning next day to our encampment, I discussed the experience with Welsh over a supper, showing him sketches I had made of the terrain and the curious rituals at the cave. He had some knowledge of the place and could explain something of what I failed to comprehend. This was indeed a former retreat of an ancient Hindu ascetic, the place still very sacred to them. Five hundred years ago, however, a sufi priest from Arabia arrived, choosing the self- same spot for his sanctuary. Since then, it has become a holy site for both religions. For the most part the two faiths share the ground peaceably out of respect for its mutual sanctity.

The sufi priest, Baba Badun (hence the name of the hill) had journeyed from the Arab lands to preach Islam to the peoples of India, bringing with him coffee plants from the port of Al-Mokka. Baba Badun then encouraged local people to plant coffee on the hill slopes as a gift from his God for their kindness to him. His preaching never caused offence for he spoke only good words about his Hindu brethren. Thus, a singular religious unity has always existed in this place, which is not always found elsewhere.

I observed to James that, whilst the priest was indeed ancient, he could not be five hundred years’ old lest he be Methusaleh himself! He laughed heartily at my ingenuousness. A priest called Baba Badun has always lived in the hermitage for, when one dies, a disciple takes on the duty. It seemed my doubts have been answered. Or have they? I still believe that something else was transpiring at the cave, something decidedly secular in nature. I keep my concerns to myself for the time being.

Drawing of the tiger by James Welsh 1805

[from Military Reminiscences of Col. Welsh Vol I]

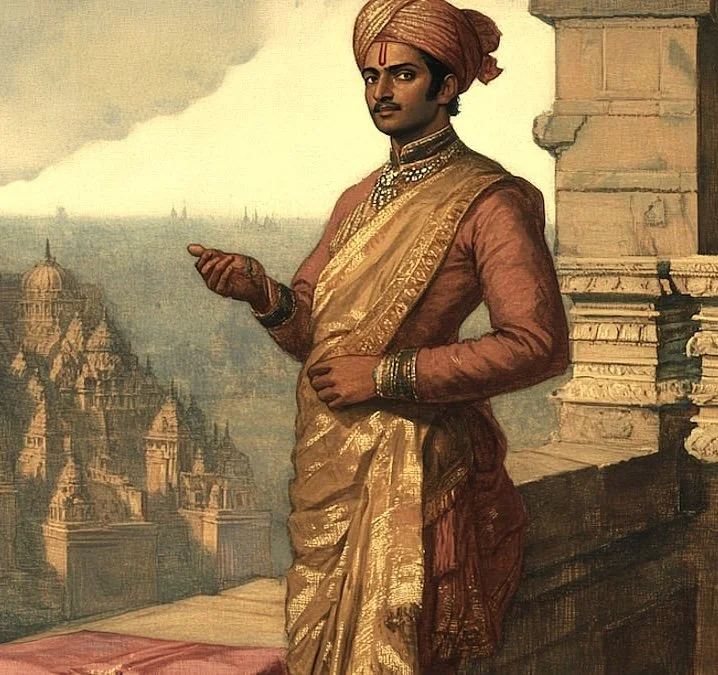

Sultan Krishnaraja of Mysore

[Picture Credit: www.dharmadispatch.india]

Mugger crocodiles of Tennaserim

[Wikimedia Commons]

2nd February Tinghully (30 miles from Bababoodun)

Arriving at the shore of a great lake, Tinghully Tallowe, we camped by a village where the local inhabitants sought our aid. A fierce tiger had been sighted, ten men and many bullocks already lost to its fierce jaws. It was too good to miss. How could I visit India without a hunt? The lake is vast and deep, rich in waterfowl. At the lower reach where the bank is high, marshy ground gives way to dense jungle. It was believed the tiger’s lair lay in this forest. Early this morning the officers and a few sepoys (the majority not yet returned from Baba Badun) set out in two parties led by James and Captain Pepper respectively. We found the den easily enough by following a trail of bones and well-picked carcasses. It was deserted. Our tiger was on the move.

Just then, a black panther appeared across our path, boldly sauntering directly between the two parties. Whether by its guile or sheer chance, we found ourselves unable to take aim lest we accidentally shot one of our own- or alerted our tiger. The beast was thus spared. It seemed our hunt today might prove fruitless. Not so. Whilst we had been wandering in the forest, local men had sunk a deep hole in the ground with a sheep tied to a sharpened iron spear at its base. Its pitiful bleating must have drawn the tiger out for all at once he had leapt down into the hole and now lay mortally impaled. Roaring in anger and pain, the beast struggled hopelessly to tear itself from the spike, only worsening its wound. From the safety of above, the villagers took further potshots with stones and clubs.

Alerted by the dying roars, we hastened to the source, only to discover we had missed the fun. The joyful villagers were already processing home, bearing the monstrous beast on bamboo poles. It was my first sight of a tiger at close hand. I must admit, I felt mightily relieved we had not come upon him in the wild for we would surely have lost a few men before downing him. The animal was enormous: each paw larger than a dinner plate, his head alone three feet in circumference. On its hind legs, he would have dwarfed us all. Both Captain Welsh and I took the opportunity to sketch the fellow; James imagining him as in life, while I preferred to reflect on the poignant death of such a mighty creature brought low.

February 29th Mysore (100 miles south of Tinghully)

Our men have returned from their visit to the celebrated saint with renewed vigour. Still mulling over what I witnessed, I sought out Havildar Rajoo to ease my lingering concerns. His answers were plausible enough. The current leaders of the different Maratha factions –Daulat Rao Scindia and Jashwant Hostia – have recently individually visited the shrine to pay their respect. This was known to our men. Rajoo admitted there were still those who wished for war. Yet the seer had personally dissuaded them from further hostility against the British. He claims the gift of foresight, warning that rebellion against the Company will fail. It is fated that for now the British be in the ascendancy. He promises, however, that one day this will change but the time has not yet arrived. My intuition had been right; more was discussed than spiritual matters. And yet, the havildar does not entirely convince. Is he gulling me?

The next encampment was near Seringapatam, Tipu Sultan’s old capital and the site of his last stand. There we met Major Wilks, now Resident of Mysore, accompanied by the new twelve-year old sultan of Mysore, a descendant of the Hindoo Wodeyar dynasty who had ruled before Hyder Ali and Tipu Sultan, who has been graciously allowed to ascend his rightful throne. For the past six years, Major Wilks has taken responsibility for the boy’s upbringing. He has done a remarkable job. Sultan Krishnaraja is a handsome youth, educated and accomplished, a young Moslem ruler with the manners and bearing of an English gentleman. I could not help but recall, however, Tacitus’ famous remark about it being the blandishments of Roman civilisation that finally defeated subject peoples, not the wars that conquer them. I thought then of my own mother and our island with a sense of foreboding. Would all that was truly the Straits one day be replaced by this foreign culture from far away?

Yet, I cannot deny but we have been royally entertained in Mysore. There have been formal dinners, riotous processions, strange religious rituals, entrancing dancing girls galore, and even horse races to enjoy, for the young king has been eager to show off his equine skills. Major Wilks has been the most attentive host. The week of entertainment was crowned with a final honour: the presentation of the battalion colours to Captain Welsh respective of his new command. I suspect my brother-in-law is tipped for a majority. It is high time he was promoted, in my opinion, for he is the most assiduous of soldiers and a great leader of men.

5th March Oonasy

Today we stopped in the heat of the day by a small gully near the village of Oonasy to water the horses and take shade. While the horses drank, our sepoys took the opportunity to wash clothes and bathe, the officers lounging under awnings on the bank. To our horror, a horse was suddenly dragged into the deeper courses of the river by unseen hand. It appears a huge crocodile had been observing our presence and took its chance. The sepoys splashed after it, screaming both in terror and anger and unbelievably, managed to retrieve the poor animal from its jaws. It proved too badly injured to survive, so was quickly dispatched by bullet. The crocodile merely beat the water with its mighty tail and submerged once cheated of its meal.

The incident caused us great distress. These riverine crocodiles –muggers –are rarely found alone. They live in packs, lurking in the depths or basking on river banks, concealed by their muddy colouring. Although it was midday and fiercely hot, Welsh and Pepper led a detachment to search the nearby embankment. To our horror, we discovered the crocodile’s lair was but a short distance downstream near the shallows where we had earlier forded the river.

As if to mock us, the creature watched from the opposite bank, its enormous jaws wide open in a fearsome yawn, as if taunting us by its lack of concern. The savagery perpetrated on the poor horse instantly drove my rage. I took aim, as did James Welsh; we both fired as one. A single ball passed through the mugger’s ugly head, immediately putting an end to its wretched existence, whether by my shot or that of James, I cannot say. At the report of our gunfire, several other monsters slithered into the river, quickly out of range, requiring only a lazy flick of their strong tails to disappear. It was a timely reminder that our guard must never be down. Only Providence had saved us from a dreadful culling.

10th March Guzzlehutty Pass (50 miles from Mysore)

Finally, we descended the mountains that separate Mysore from the Carnatic plain through the wild and beautiful Guzzlehutty Pass. Of all the magnificent views we have so far witnessed, this is the most awe-inspiring of all. Despite the different climate and the dry terrain, one would be forgiven for imagining that we were on a high pass of the Swiss Alps. The Guzzlehutty is akin to standing on the rooftop of the world. As we began our descent, made more difficult by the challenges of the rocky and treacherous terrain, we chanced upon an abundance of game and were sorely tempted. But we pressed on. It was essential to reach the valley below before nightfall.

These paths were never intended for an army on the move, yet our sterling lads worked hard to lower the guns and wagons safely, even entire sick carts, for which Captain Welsh rewarded them with twenty sheep. They were well deserving of it. Now on home soil – for they are a Madras regiment recruited largely from the Carnatic –our men were ecstatic, rejoicing and weeping, throwing themselves down to kiss the very ground. It was an astonishing spectacle that these usually hardened sepoys should be so moved by emotion. James informs me this is different from the amor patriae that a British man feels for his native land. Sepoys feel little attachment to India itself; it is the soil of their home villages to which they cleave. The Carnatic is their mother.

The heat on the plains is markedly greater even than before; the sun burns relentlessly. However, it is still a charming region watered by fine rivers and known for its pasturage, particularly famed for its sheep, said to be the finest in the entire land. The march to Madura, the main city of the interior, is expected to be uneventful. We are but two hundred miles to the fort, but spirits are high, and the road is easy from here on. The end is in sight.

27th March Palmacottah

Madura to Palmacottah has been tedious, through a wide plain of endless cotton fields. The only interesting occurrence was the arrival of the families, joining us in straggles, each one greeted with rapturous reception. It is the custom for troops in their home territory to establish an encampment around the fort for wives, children and the old as a reward for their long estrangement. But at a time when we wished to make haste over the final miles, we have been forced to dawdle.

Yet here we are at last. After three long months upon the road, countless adventures, nine hundred gruelling miles, across mountains, rivers and plains, we are now settled in the fort of Palmacottah to relieve the departing 16th. I have lodgings in the Commander’s own house and now have ownership of a decent pallet in a room of my own. Forgive me if this entry is short. I am at last to my bed.

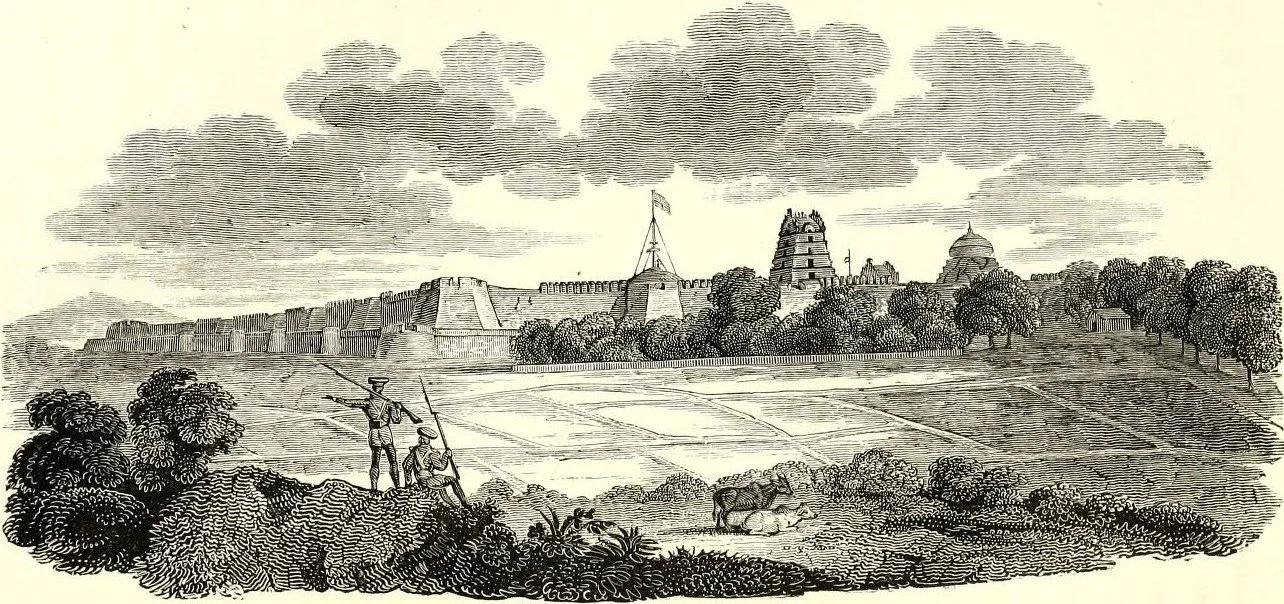

Fort Palmacottah, Tinnevelly District, The Carnatic 1806

Artist: Captain James Welsh from ‘Military Reminiscences Vol I by Col. James Welsh’.