Part Three: The Iberian Peninsula

A vast array of players people the pages of this section of the novel, many of whom lived fascinating or tragically short lives, too many to be included here. Instead I have included pen portraits of a few who particularly encapsulate the brutal events. I have also taken the liberty of including one brave woman who sadly did not make into to the novel, except in passing, but whose story and spirit almost beggar belief…

All five Napier brothers make an appearance at one place or another in various sections of Legacy but the three eldest: Charles, William and George, ‘Welliongton’s Colonels’ make the greatest contribution. They were close to William Light during the years of the Peninsular War and remained friends afterwards, especially when Light became a member of their family on his second marriage. In their day, the Napiers were both war heroes and society favourites despite not having much money. They did, however, have aristocratic connections, their mother Sarah Lennox Napier being the sister of the Duke of Richmond who had great holdings in London and the countryside. In later life, somewhat embittered by their lack of opportunity (as they saw it) after the end of the Napoleonic Wars and because they were inclined to liberal opinions, they often found themselves in opposition to the government of the day.

The Brothers Napier

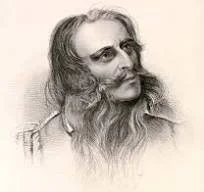

Lt. Col. Charles James Napier (1782-53)

Seriously wounded at the battle of Corunna in 1809, Charles Napier was left for dead on the battlefield but miraculously a French drummer brought him to the headquarters of the French general, Marshal Soult, who made sure he had the best medical care available. He was a prisoner of war, but Soult generously allowed him to return home to convalesce after he gave his parole (word of honour) to return to captivity when he was better. Charles did return - but to the war not to prison. In January 1811, he received a disfiguring facial wound which ruined his handsome good looks. For the rest of his life he wore heavy facial hair to hide the scars.

After the war he fell out with the Prince Regent and because generally disenchanted with the state of Britain, particularly the government failure to address poverty and injustice to the ordinary people.

Appointed Governor of Cephalonia in Greece in 1822 (probably to keep him out of the public eye), he developed an abiding love for Greece and became firmly committed to the cause of Greek Independence from the Ottoman Empire, something the British government were trying to ignore.

In later life he returned to the army in India on the troublesome north west frontier, a life he preferred to administration and politics, securing many great victories, notably as Governor of Sindh Province (1844), but even there he was constantly at odds with Governor-General Lord Dalhousie. It is said that after the capture of Sindh, he sent the famous message in Latin ‘peccavi’ ( ‘I have sinned’) which has since been taken to indicate his opposition towards many aspects of British policy in India (which is on record), including his own campaign. The pun, however, was not in fact coined by Napier but by an English lady, Elizabeth Winkworth, who sent it herself for publication in Punch magazine; they chose to knowingly print it as Napier’s own words!

A statue to Charles Napier still stands today in Trafalgar Square, London.

Image courtesy of Wikipedia Commons (Andrew Shiva)

an engraving by William Egleton during the Peninsular War

The Governor of Sindh (unknown artist)

William Francis Napier (1785-1860)

Known for his aquiline good looks and his athletic build, William Napier was more high-spirited than his elder brother, and was known for his sense of humour and daredevil courage. But like all the Napiers he was high-minded; he detested injustice, and was easily moved to tears. He spoke out strongly in favour of the Emancipation of Slaves, a cause which he especially espoused. Although a ladies’ man in his youth, William remained resolutely faithful to his wife Caroline Amelia Fox once they married in 1812.

William was seriously wounded at the disastrous action at Casal Noval in 1811, taking a bullet to the spine, which was subsequently never removed. It caused him great discomfort throughout his life. Napier always attributed his survival to the arrival of William Light who saved both William and his younger brother George who were stranded injured behind enemy lines. They remained close friends from then on.

William subsequently became a Lt. Colonel and was given command of his regiment, the famous Light Brigade, on the death of its founder General Robert Craufurd. But by Waterloo and the end of hostilities, William had grown disenchanted with military life. He devoted the rest of his life to painting and writing, for which he became celebrated, notably for his great work in several volumes: ‘A History of the Peninsular War’.

Throughout his life, he espoused liberal causes and democratic views, even putting aside his distaste for politics by campaigning for the Reform Bill of 1832 to widen the vote and redistribute parliamentary seats. A statue of William Napier (by George Gammon Adams) stands in the crypt of St. Paul’s Cathedral.

[Photo credit: Wikipedia Commons, contributor 14GTR]

Colonel William Napier c. 1812-15

General Sir George Thomas Napier (1784-1855)

Wounded in the wrist at Casal Nova, he first met William Light when stranded with his severely injured brother behind enemy lines. At the storming of Ciudad Rodrigo in 1812, George lost his right arm, the third bullet in the same limb. Notwithstanding, he learned to fight with his left. Ebullient and irrepressible as a young man, George did not deal well with his convalescence back in Britain although he did meet and marry his beloved wife Margaret during this period.

Back at the front in 1814, he served with distinction throughout the Peninsular War but after the death of his wife in childbirth in 1819, he resigned his commission, remaining at home to take care of their four children before resuming his military career when they were grown. After receiving his knighthood in 1838, George was appointed Governor General of the Cape Colony, during which time he oversaw the abolition of slavery and established Natal as a British colony driving out most of the Boer community. ; the town of Napier is named for him. His son, William, published his autobiography in 1885, which mostly encompasses his experiences in the Peninsular War.

George Napier died in Geneva in 1855; his family erected a commemorative plaque in his honour in the Holy Trinity Church.

[Photo Credit: Wikipedia Commons, The Lonely Pather]

Miniature of Col. George Napier (his right sleeve pinned) by Francois Sieurac (1814)

Lt. General Sir George Napier, Governor-General Cape Colony

Sir Arthur Wellesley, The Duke of Wellington (1769-1852)

A younger brother of Richard Wellesley, Governor-General of India (1798-1805), was an Anglo-Irish military officer who became one of the great figures of the early nineteenth century. Still fairly inexperienced when he first received command in India, helped by his brother’s patronage, newly promoted Colonel Arthur Wellesley soon proved himself a leader of astonishing vision and leadership. After victory against Tipu Sultan at the battle of Seringapatnam, he was Major-General Wellesley was given command of the entire British army in India in the conflict against the fierce Marathas of the Deccan who had allied with the French. In a series of brutal engagements, they were finally overcome. At the same time French ambitions in India were finally ended. Wellesley later wrote that his battles against the Marathas were the hardest he ever fought.

In 1809, Wellesley was awarded command of the British forces to drive the French out of Portugal during the Napoleonic War, the onset of what came to be known as ‘The Peninsular War’. Between 1809-1815, Wellesley systematically pushed the French first out of Portugal and then over the Pyrenees back into France before leading the chase which was to eventually end at Waterloo in the greatest battle of the age. The genius and humanity of Wellesley, now the Duke of Wellington, made him a hero to both the soldiers, the ordinary people and the politicians back home. His popular nicknames from The Iron Duke to Old Conky (on account of his long nose!) demonstrate the warmth of feeling. Nor can his achievements be underestimated: Napoleon’s Grande Armie was twice the size of the British forces in the Peninsula.

Wellesley was a complex man, proud and mercurial but at the same time practical-minded and abstemious in his personal life (other than in his love of fine clothes, even on campaign) As a commander, he won the hearts of his men by always sharing their conditions and ensuring to the best of his abilities that they were fed, sheltered and given adequate clothing and boots. he is known to have wept on the filed in the aftermath of battle when the toll of dead and injured was particularly grave, such was the depth of his attachment to the men he commanded.

After the war, Wellington returned to Parliament, serving as Prime Minister 1828-30 and again in 1834 but his Irish affiliations for Catholic Emancipation ultimately proved damaging to his political popularity, although he led the opposition for many years. On his death, the outpouring of grief from all sections of the community was umprecedented.

He was granted a state funeral, attended by vast crowds both in St Pauls’ Cathedral and lining the roads along the way. Queen Victoria even referred to The Duke of Wellington as ‘the greatest man this country ever produced’.

The First Duke of Wellington by Thomas Lawrence c. 1815-16

[Picture credit: English Heritage: The Wellington Collection]

Wellington at Waterloo by the illustrator William Heath

[Picture Credit: The British Library]

The funeral of The Duke of Wellington passing his home, Apsley House 1852

By Louis Haghe

[Photo credit: The National Army Museum Collection]

Susannah Dalbiac (1784-1829)

In an inevitably testosterone-heavy section of Legacy, I am purposely including Mrs Susannah Dalbiac whose exploits challenge many of our presumptions about the behaviour of women of the period., particularly in wartime Also as a northern girl myself, I have to agree with her husband, who believed it was his wife’s northern grit that made her so special!

Susannah Isabella Dalton was born in Ripon in Yorkshire although– typically– little is known of her early life until 1805 when she married Major James Charles Dalbiac (1776-1847), commander of the 4th Light Dragoons. When William Light bought his own lieutenancy in 1808, he served under Dalbiac and was in this regiment off and on during his entire time in the Peninsula.

A number of married women accompanied their husbands to Portugal when the campaign first began, staying well away from any theatres of war in family lodgings in cities such as Oporto or Lisbon. Susannah Dalbiac appears to have originally been stationed amongst these other army wives.

She made her first active contribution to the war, however, in July 1811 when Susannah learned Major Dalbiac was seriously ill with Guadiana fever that had been running riot through the army. Aware that doctors were already struggling with casualties of war and that little care was available for men with fever crowded together in insanitary conditions, she took it upon herself to travel to the front. There she not only nursed her husband back to health but also stayed to assist in the hospital wards, tending to men suffering with this debilitating malarial fever. Conditions for the sick and wounded were generally appalling but Susanna did her best to nurse men or comfort them in their final hours.

From then on, Susannah remained with the army, travelling as a nurse from campaign to campaign. At the battle of Salamanca in 1812, while she was assisting with the injured in the rear, Susannah heard that Major Dalbiac had fallen in one of the cavalry charges. With no thought for her own safety, Susannah rushed forward into the maelstrom of the battle in the vain hope that she might find him. She discovered a scene of utter hell - bodies piled high, the dead often covering the living. As she searched for Major Dalbiac, she organised the evacuation of any wounded she uncovered.

At one point, she was almost run down by another cavalry charge; an infantry soldier realised her vulnerability and risked his own life to drag her behind a discarded cannon until it passed. Unbelievably, she finally did find her husband, unconscious but not seriously injured. He would likely have bled to death, however, if he had not been rescued.

After this great British victory, Wellington’s army entered Madrid in a triumphal procession in which Susannah Dalbiac herself was including, riding in an open carriage, such was the respect in which she was held. James Dalbiac, after over twenty years as a serving officer decided that enough was enough. He had done his duty to his country; it was now time to do his duty to his wife, without whom he would not have survived so far! He resigned his commission and the couple returned to England.

The Dalbiacs settled at Moulton Hall near Richmond in N. Yorkshire where they raised their daughter, Susanna Stephania (1814-95) who became Duchess of Roxburgh, one of Queen Victoria’s longest-serving ladies-in-waiting. In 1822-4 Dalbiac returned to active service as a Brigadier-General in Gujerat with the Bombay army. It is not recorded whether Susannah accompanied him to keep him our of mischief!

Unsurprisingly, no image has survived of Susannah Dalbiac. This portrait is of her daughter Susanna Stephania Innes-Kerr, Duchess of Roxburgh, painted in 1868 by Henry Wyndham Phillips. [Photo Credit: The Royal Collection]

Major James Charles Dalbiac

[Photo Credit: Floors Castle. Roxburgh Estate]

“An English lady of a gentle disposition, and possessing a very delicate frame, had braved the dangers and endured the privations of two campaigns … In this battle, forgetful of everything but the strong affection which had so long supported her, she rode deep amidst the enemy’s fire, trembling, yet irresistibly impelled forwards by feelings more imperious than terror, more piercing than the fear of death”