The Faces of William Light

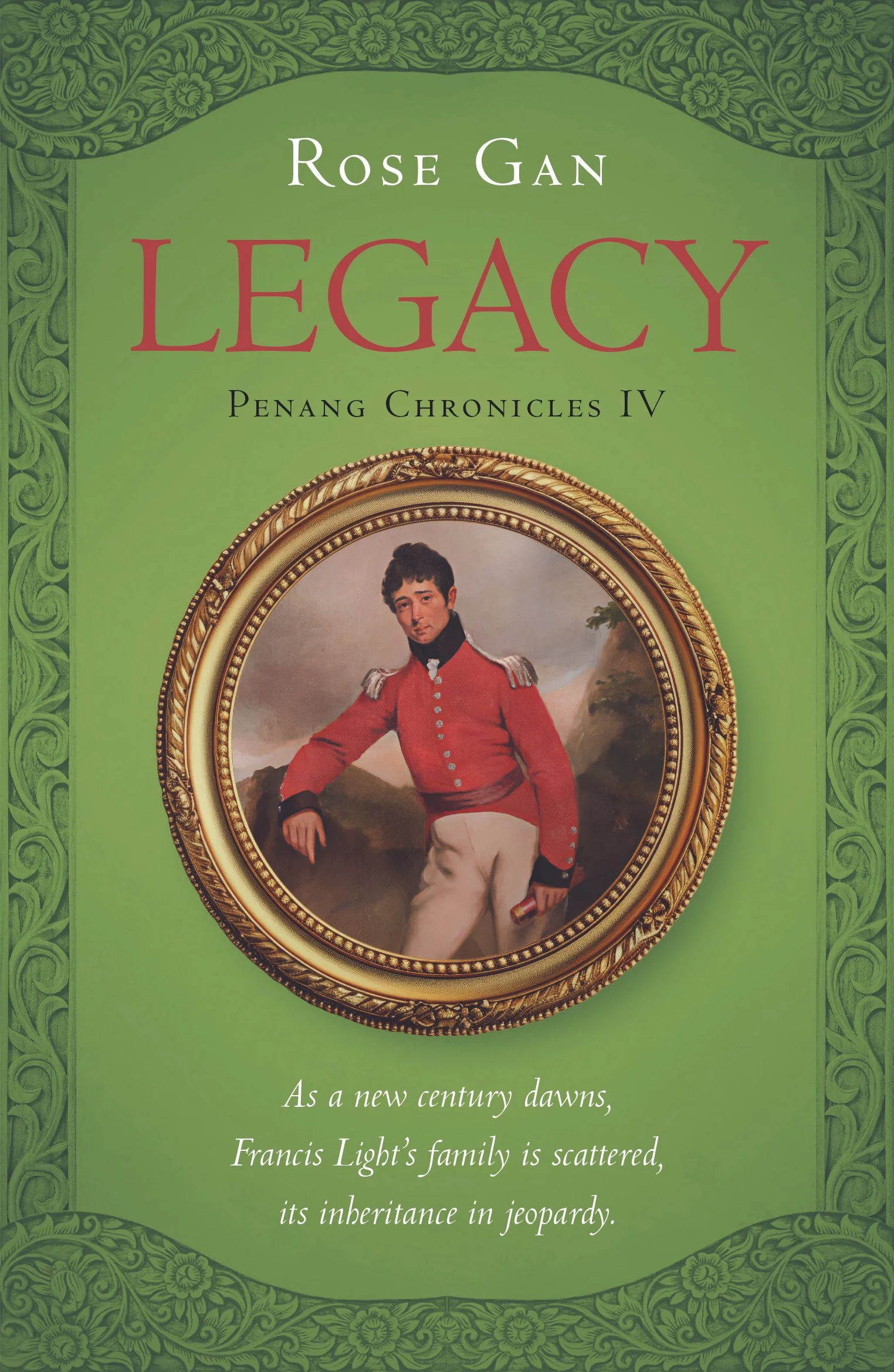

Legacy. Penang Chronicles IV

Published Sept-Nov 2026

Monsoon Books UK

One of the major themes of my fourth novel Legacy is identity, particularly for those of mixed heritage. At this period it meant either spending their lives passing as white –and thus in denial of their true selves–or accepting the inevitable secondary rank within whichever society in which they choose to live. William Light was himself sent back England at the age of 6 to be raised entirely in Suffolk, subsequently spending very little time in the East. One imagines this was an intentional decision to raise him as a British gentleman in every way possible so that he ‘fitted’ into the required mould. His father Francis Light, fully intended to return home shortly afterwards with his entire family, and ensure they were all entirely British. His untimely death prevented this. Instead, William never saw his family for many years, his family life limited to infrequent letters.

His early career proceeded in a very conventional pattern: lieutenant in the Royal Navy whilst still in his teens; an officer on Wellington’s own staff during the Peninsular War; friend and contemporary of famous British aristocrats such as the Napier family; a familiar of Byron and Shelley in Italy; a marriage to the daughter of the Duke of Richmond; and a man about town in London. Ultimately as Surveyor-General of South Australia he is credited with the foundation of the beautiful city of Adelaide, becoming a colonial figure of note. It seems that his parents’ sacrifice had indeed resulted in a fine career within the British hierarchy for their eldest son.

Yet, close examination of his life reveals a lonely man who spends long periods of his life drifting aimlessly along, frustrated by his continued lack of preferment despite his acknowledged extraordinary skill, regarded by many of his peers as an outsider, a man unable to feel anywhere to truly belong. Despite his achievements, William Light’s status as a man of mixed heritage without fortune and with virtually no family connections whose temperament was unfairly suspected of being unreliable. Light spent his entire life struggling in vain against privilege, patronage and prejudice, those three unforgiving icons of Imperialism. In the following depictions of Light –several of which are by the man himself with some assistance from the famous English master George Jones R.A. – we observe an artistic version of this identity crisis.

In the earliest portrait (featured on the cover of ‘Legacy’) Light is a youthful army officer, striking a jaunty pose against a background of rural England, a conventional choice for such portraiture. He sports dress uniform (worn informally without headgear) and carries a telescope, the symbol of his army service as a surveyor and scout during the Peninsular War. Light is shown as confident, even a tad arrogant, his dark tousled hair worn in the fashion of the early 19th century. His features are sharp, his lips full, his skin is fair and his cheeks rosy, the epitome of a young British officer about town.

The date is circa 1815-16 in the aftermath of the final defeat of Napoleon at Waterloo, when William Light was twenty- nine years old. It is how William Light wished to present himself to the world: the son of the founder of a British settlement in the Indies, an army officer of distinction, a gentleman about town who was close companion to members of the nobility.

It is not known for sure who painted this portrait because the image is unsigned. It has been suggested that it may have been a self-portrait because of what appear to be preliminary sketches amongst Light’s papers (the accompanying image above). Here we see the same pose but much less elegantly executed. Light was a competent landscape artist but by no means a figurative painter, yet the finished portrait is a very fine piece of work and the young man a more polished figure. Perhaps George Jones himself contributed to the final version, bringing a master’s touch that is not apparent in Light’s own work. In comparison to his other self-portraits, it is a much more accomplished piece. Yet the sketch may be a truer reflection.

What might have been the purpose for such a fine portrait of a young man of slender means who possessed no property in which such a work might hang? Perhaps it was originally painted in Jones’ studio where it would have been on view to all those other important people whom the famous artist painted. Jones, like Light himself, was a friend of the Napiers. It is likely they moved in the same circles. Such an accomplished portrait would certainly have brought Lieutenant Light to the attention of society at a time when officers in his position were struggling to gain a suitable commission, the typical fate of military men in a time of peace. Was this painting executed as a means of self- promotion, creating an image of himself that was grander and better connected than he actually was? We are familiar today with how images can be distorted by applications and AI; the art of portraiture was similarly vulnerable to presenting false or more desirable impressions!

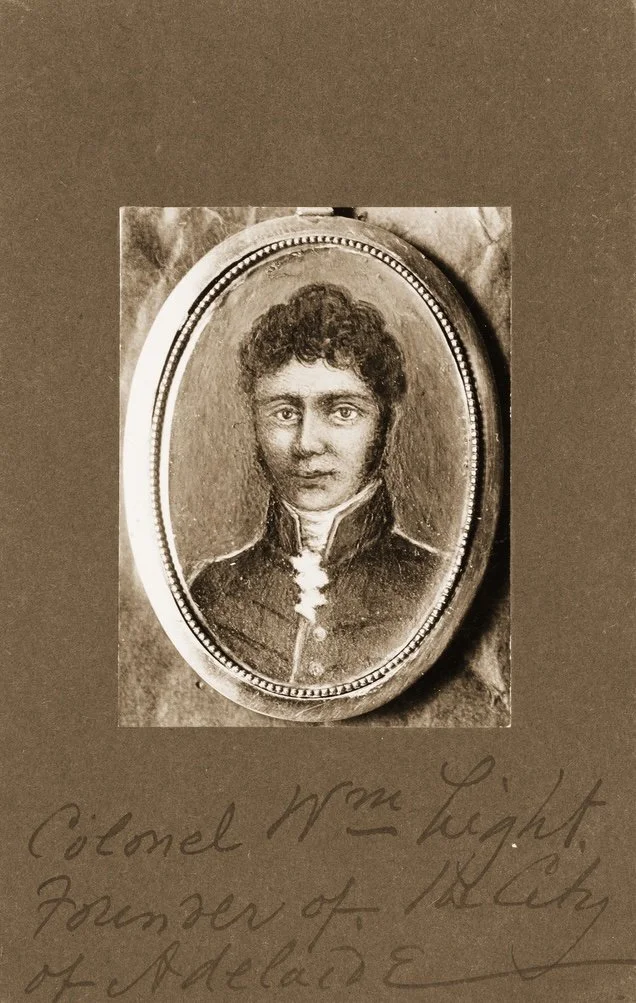

This miniature is dated sometime after 1820; this black and white photograph of the original is mounted on card with a later description. Here Light is still a young man, a little less gaunt than in the 1815 portrait with curlier hair and less angular features. Five years of peacetime service in various garrisons around Britain and Ireland could do that to a man – he has filled out somewhat. His eyes are luminous and his face appears more sallow but without the original miniature itself, it is difficult to be sure. This may indeed be another Light self-portrait, but as it is not reminiscent of Light’s style, it may equally have been the work of someone else.

Why might Light have sat for a miniature at this point in his life or have produced his own image for a loved one? There is something more intimate and familial about miniatures, different from the public nature of a grand portrait meant to hang in public. Whilst stationed in Ireland, William Light married Miss E. Pérois at Londonderry on 24 May 1821. At the time of their wedding, Light’s regiment had received news that they were soon to be posted overseas to India. It is tempting to speculate that this miniature might have been a private wedding gift for his new bride. It would have been a typical intimate gift from a soldier to his young wife. In any event, Light ultimately resigned his commission, choosing instead to spend time with her on a Grand Tour of Europe. Sadly, this did not come to pass. By the following year his wife was dead, although we know nothing about the cause of her untimely passing.

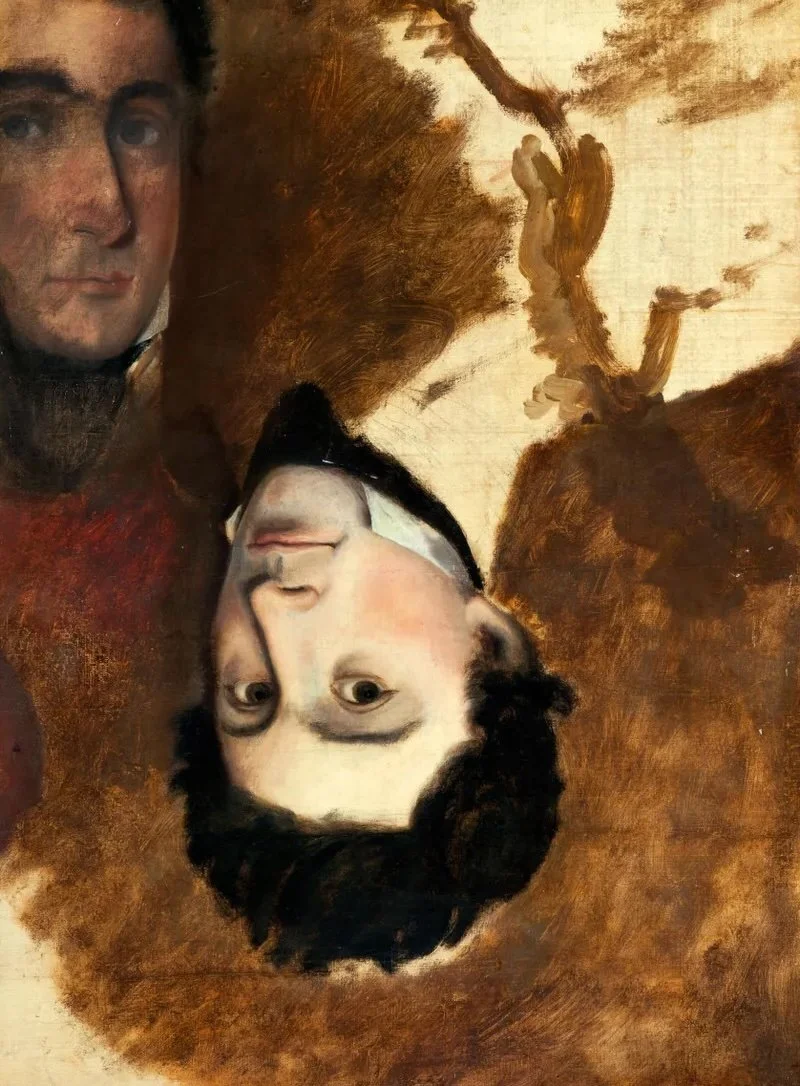

Our fourth image hangs today in the National Portrait Gallery in London, painted by the same George Jones mentioned earlier, as can be seen by his signature. The date of this piece is uncertain. We can speculate, as it refers to Light as ‘Colonel’ that it must have been painted after his service in Spain, so at the earliest in 1824. By then, Light was thirty–seven years old. He had been gravely injured in the ill-fated Spanish adventure under General Sir Robert Wilson and subsequently spent months in prison in Corunna held in dreadful conditions, his wounds largely untended. Colonel Light had been fortunate even to survive the experience, but it was to have severe repercussions for him, permanently damaging his previous rude good health. It is most likely he caught tuberculosis during this imprisonment, a disease that was incurable at the time. It was ultimately to cause his premature death in 1839.

Another interesting feature is the legend: ‘Colonel Light, Founder of Adelaide, S.A., written in the same hand as the signature, so suggesting George Jones himself. Was this portrait perhaps painted before he left for Australia in 1836 when it was likely he would never return to Britain again? It is certainly an older man than that of the earlier pictures. Light looks thinner than ever as would be expected been after his traumatic experiences in Spain, his deteriorating health and the strain of the failure of his second marriage. There is a possibly a touch of grey in his dark brown hair. Whilst still a handsome man, he appears more frail than earlier portraits. We can see his striking eyes more clearly: they are large (as in the miniature) but even more glassy; and we can now identify the colour– brown. It was suggested by Dr. John Miller Tregenza (1931-99) authority on the life of William Light, that the shining eyes might be a symptom of consumption (tuberculosis), a common side effect of the illness. For the first time, Light’s skin tone here also appears swarthy. Is this a more honest rendering of William Light in which his mixed heritage is acknowledged?

In 1824, William had married again, a rich heiress Mary Bennet who was the illegitimate, but recognised, daughter of the deceased 3rd Duke of Richmond, Charles Lennox. Mary Bennet was cousin to the Napiers; she had met William in their company. It is entirely possible that George Jones executed this portrait at that time when William and Mary were together in London before they set out on their very lengthy Grand Tour, or perhaps during the summer of 1837 when the couple returned to England for a few months after a period in Italy, thus accounting for his darker complexion. Mary Bennet was rich enough to commission such a work. The legend may have been added to the original portrait at a later date, perhaps even after Light’s death. The phrase ‘Founder of Adelaide’ certainly has the ring of memorialisation. Or perhaps Jones painted it from memory with reference to his earlier sketches on the news of Light’s death, as a tribute to his former pupil and friend?

Finally, we have a self-portrait that was most probably painted in Adelaide; a preliminary sketch is owned by the Mayo family, the descendants of Maria Gandy and her husband Dr. George Mayo. It may have been executed in 1839 after the fire that destroyed so many of his personal effects. It is an unfinished and roughly executed piece that shows evidence of an earlier version in the bottom right hand corner, whose features are distinctly different – and much darker toned.

This is a fascinating insight into Light’s state of mind in the final year of his life. The execution is rushed, the picture is ultimately unfinished and the earlier version (which seems much more carefully rendered almost looks like a different man. He is older, darker skinned and yet more robust. Are we seeing Light has he might have been before his illness finally ravaged him? Has he decided towards the end to show himself as he really is, haunted, wasted and yet with aspects of his earlier self? This piece of work only adds to our conundrum.

Here Light is older and more gaunt, although his skin is ghostly pale and sallow. His hair has no trace of grey although it is unkempt and shaggy compared to earlier images. Yet there is a wry expression on his face, an enigmatic knowingness that draws one in. This painting may well have been an unfinished piece that he was working on in the months before his death, reflecting his wasted frame and waxen skin and feverish cheeks. We know he was also plagued with fevers and other ailments at this time. His hair is more unkempt than usual, although he is portrayed wearing formal neck attire; we presume he intended to show his full suit had the work been completed.

By the end of his life, Light was still dogged by defamation and hostility from leading members of the community in Adelaide. Even the Reverend Howard refused to visit him in his final illness, presumably because of his unconventional relationship with Maria Gandy. This inscrutable expression may show us that Light was finally reconciled to it all, at last acknowledging his true nature, no longer interested in playing society’s game, which he by now knew he would never win? The loss of so much of his private writings – his journals, sketches, letters and other papers– in the fire in January 1839 meant we can never have a definitive answer to our speculations. Yet the mysterious second image on the unfinished portrait above shows us that we can never be quite sure of the accuracy of any depiction. An image is only as faithful as the artist (or sitter) wishes it to be!